How China Weaponized a Trillion-Dollar Surplus Against the World - Part I

Image by AlJazeera

Executive Summary

The Great Trade Hijack: How Beijing Outsmarted Western Barriers

Picture this: while the West was building tariff walls to keep China out, Beijing was busy tunneling underneath them. In 2025, China hit an astonishing milestone—a merchandise trade surplus exceeding 1.07 trillion dollars—the largest any single nation has ever achieved.

This is not luck. It is the outcome of a calculated, audacious strategy: flood the world with exports, starve imports at home, and when tariffs slam one door, kick open a dozen others across Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Breaking the Tariff Code: Inside China’s Supply-Chain Masterplay

The conventional wisdom says tariffs should crimp exports. Instead, they’ve become a perverse catalyst.

US and allied duties pushing past 30 percent didn’t slow the surplus; they turbocharged it by forcing Chinese firms to pivot toward ASEAN, India, Africa, and Latin America—markets hungry for cheap manufacturing, green technology, and industrial inputs.

Through a mix of legitimate trade diversion, sophisticated supply-chain embedding, and outright tariff evasion via trans-shipment hubs, China has transformed every barrier into an opportunity.

The Surplus That Changed Everything: Why 2025 Will Be Remembered as a Trade Inflection Point

Yet this triumph contains the seeds of its own backlash.

Global partners are waking up to a trade system they no longer recognize. Europe is tightening its defenses.

Emerging markets are slapping tariffs on Chinese goods to save their own industries.

The question is no longer whether China can sustain this surplus, but whether the world will allow it to.

Introduction

When the Factory Becomes a Fortress: China’s New Trade Strategy

From Factory of the World to Surplus Superpower

For three decades, we’ve heard the same refrain: China is the world’s factory. But factories produce goods. Surpluses are about power.

And right now, China is wielding both in ways that are starting to terrify policymakers from Brussels to Washington to New Delhi.

Beyond the Tariff Wall: Why China’s Export Machine Only Got Faster

In the first eleven months of 2025, China’s merchandise surplus rocketed past the trillion-dollar mark—1.07 trillion dollars, to be precise. For perspective, that’s larger than the GDP of Russia or South Korea.

It shatters the previous full-year record of roughly 992 billion dollars set in 2024.

And this happened at a moment when US tariffs on Chinese goods were hovering near 30 percent on average, with some categories facing levies exceeding 100 percent.

Tariffs that were supposed to cripple the Chinese export machine instead supercharged it.

The Remaking of Global Trade: How Beijing Seized the Initiative

This inversion of expected cause-and-effect is the story of our moment.

On the surface, it looks like simple arithmetic: exports up, imports flat, surplus explodes.

‘A Billion Factories, One Trillion Dollars: China’s Unrelenting Ascent- Quote Dr. Bhardwaj

But beneath the numbers lies a more unsettling narrative about how China has reorganized its entire commercial apparatus to survive and thrive under siege.

Here are a few facts.

(1) ASEAN factories running on Chinese components.

(2) African ports and Latin American supply chains becoming Beijing’s new trading grounds.

(3) China conclusion the Western-led order was no longer in its interest, and decided to build a new one around itself.

From Dependence to Defiance: China’s Strategic Pivot

The irony cuts deep.

The very tariffs meant to “decouple” the West from China may have instead accelerated Beijing’s decoupling from dependence on Western markets—and created something arguably more destabilizing: a China more globally integrated, more diversified, and more determined to remake international commerce in its image.

Key Developments

The Exports Nobody Expected: How China’s Sales Exploded Despite Tariffs

The Anatomy of a Record-Breaking Surplus

The road to a trillion-dollar surplus wasn’t paved overnight. It was built through three converging developments that, taken together, explain how China achieved the unthinkable.

The Export Rebound That Nobody Could Stop

Start with the headline: Chinese exports are surging. In November 2025 alone, dollar exports rose nearly 6 percent year-on-year, and the first eleven months clocked roughly 5-6 percent growth overall.

Over five years, the picture is even starker—exports are up about 45 percent, a tsunami driven first by pandemic-era global hunger for goods, then by the world’s insatiable appetite for electric vehicles, batteries, solar modules, and advanced machinery that only China can produce at scale.

Now here’s the kicker: this export explosion occurred simultaneously with US-bound shipments plummeting nearly 30 percent in some months under the avalanche of tariffs.

Most economies would collapse under such a shock. China shrugged and doubled down everywhere else. It was as if the tariff wall didn’t exist—it just redirected the water downstream.

The Import Collapse That Nobody Talks About

If exports are the surge, imports are the silence. While shipments exploded abroad, goods flowing into China essentially flatlined.

Import growth hovered near zero, pulled down by structural policies obsessed with self-reliance in upstream inputs, local substitution in technology, and the simple fact that Chinese households aren’t buying enough to keep import growth alive.

The European Central Bank put it bluntly: China’s policies reducing foreign component reliance simultaneously depress imports while freeing up capacity to flood global markets.

China’s genius and sinister in equal measure.

While the world worries about dependencies on China, China is systematically reducing its own dependencies—and using the freed-up capacity to export even more aggressively. This is not accident; it’s architecture.

The Geographic Earthquake That Rewrote the Trade Map

Perhaps the most dramatic development is where China’s exports are going.

The United States—once the destination for nearly one-third of China’s global surplus—is being supplanted.

Factories in Disguise: How ASEAN Became China’s Trojan Horse

ASEAN has overtaken both the US and the EU as China’s largest export destination, with shipments rising 13-15 percent and regional trade hitting new peaks.

Africa is receiving exports that are set to exceed 200 billion dollars, driven by surging demand for machinery, telecoms gear, and consumer goods. India is now one of China’s fastest-growing markets despite searing geopolitical tension.

Latin America is emerging as both a market and a manufacturing springboard.

This isn’t random. This is strategic repositioning at geopolitical scale.

The Silent Substitution: How China Unplugged From the World While Plugging In More

Beijing is essentially saying: we don’t need the West as much as you thought we did. Watch what happens when we focus elsewhere.

When Zero Means Victory: Why China’s Import Collapse Is Brilliant Strategy -Quoted by Dr. Bhardwaj

But here’s where it gets complicated.

Much of what flows from China into ASEAN doesn’t stay there.

The ASEAN Earthquake: How Southeast Asia Became China’s New America

Vietnamese and Malaysian electronics exports to the US and Europe are laced with Chinese components—Beijing has effectively turned Southeast Asia into a manufacturing extension of itself, a way to serve Western markets while nominally bypassing tariffs.

McKinsey’s analysis reveals that roughly 25 percent of Vietnam’s electronics export value now traces back to China, up from just 10 percent a decade ago. Translation: tariff walls are full of holes.

Facts and Concerns

What the Numbers Reveal—and the Nightmares They Spark

Let’s get granular about what’s actually happening. China now runs significant surpluses with virtually every major economy on Earth.

Roughly one-third of its total 2024 surplus—about 360 billion dollars—came from the US alone, with a similar magnitude against the European Union.

Europe, North America, India, and most of the developing world run persistent deficits with China in goods.

Very few nations anywhere enjoy durable goods-trade surpluses with Beijing at meaningful scale.

And the composition is shifting in alarming ways.

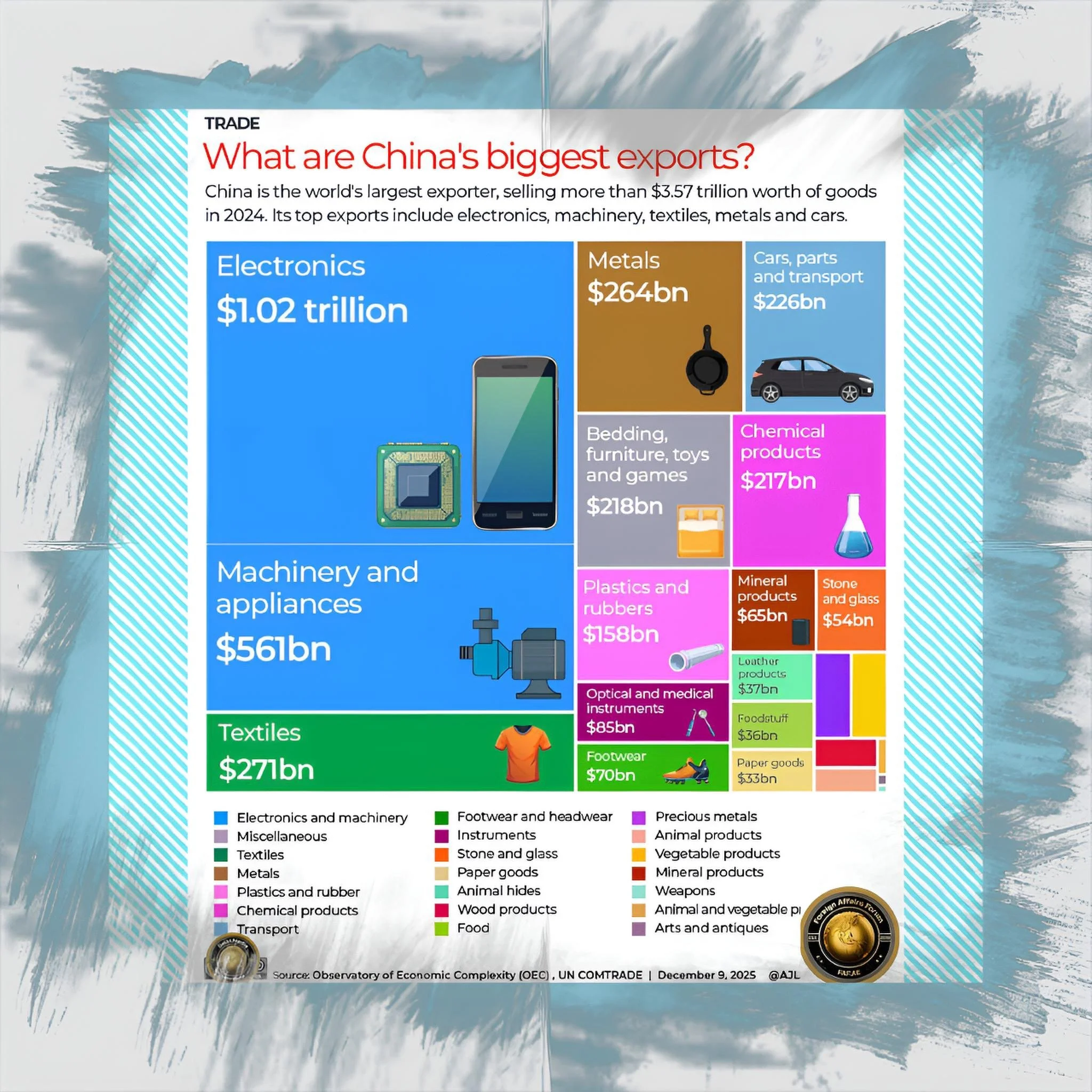

Electric vehicles, batteries, solar modules, telecoms equipment, sophisticated machinery, and an expanding slice of semiconductors have joined the traditional export mix of electronics, textiles, steel, and consumer goods.

These aren’t low-skill factory goods anymore. These are the technologies that will define the 21st century.

And China is capturing them at a scale and price point that no competitor can match.

The reason is simple but grim: overcapacity on a civilizational scale.

China’s auto industry has capacity for more than twice its domestic demand for internal combustion vehicles. Steel mills are running below utilization.

Solar panel factories could cover the world’s electricity needs multiple times over. Petrochemical complexes have far more capacity than the domestic market can absorb.

The result is a relentless pressure to export or die—to push product abroad or face cascading bankruptcies at home.

This is where the concerns begin to crystallize, and they are legitimate.

China Shock 2.0: The Nightmare Haunting Factory Towns Worldwide

The Fear of Another “China Shock”

Advanced economies are gripped by a nightmare scenario: China 2.0.

The first China shock—when US and European manufacturers got flattened by cheap Chinese competition in the 2000s and 2010s—hollowed out entire industries and cost millions of jobs.

Now, analysts at the European Central Bank, trade economists, and policymakers across the West warn that a new wave is coming.

Subsidized Chinese overcapacity will destroy margins, annihilate jobs, and trigger a competitiveness crisis in green energy, auto manufacturing, semiconductors, and advanced machinery.

German auto suppliers are already screaming. US solar firms are on the brink. Southeast Asian textile manufacturers are getting crushed.

The ECB has been particularly blunt: China’s rising surplus is the direct result of excess capacity, price wars, and the deliberate redirection of unwanted supply to hapless trading partners.

Trapped in the Dragon’s Web: How Emerging Markets Became Dependent

The Emerging Market Trap

Africa and Latin America present a more insidious problem.

These regions welcome Chinese infrastructure financing, green-energy investment, and cheap consumer goods with open arms.

But they’re simultaneously becoming more dependent and more marginalized. Chinese lending comes with strings attached. Imports grow while local industries wither.

The commodity-export-for-Chinese-manufactured-goods exchange becomes institutionalized and difficult to escape.

Steel, automotive, and textile producers across Africa and Latin America are now demanding protection from the torrent of cheap Chinese goods.

But tariffs against China anger Beijing, which holds enormous sway through finance and investment.

It’s a trap with no good exit.

The Ledger of Alarm: Why Every Economy Should Be Worried

The Origin-Washing Crisis

Here’s where it gets ugly. There is widespread evidence—documented by US authorities, corroborated by shipping data and trade investigations—that Chinese firms are engaging in systematic trans-shipment and origin washing to evade tariffs.

Products are minimally processed in Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mexico, and the UAE, then relabeled as local goods and shipped to the US and Europe.

When Numbers Lie: The Origin-Washing Scandal Threatening Trade Integrity”

The original sin

(1) Documentation is falsified

(2) Values are underreported

(3) Products sit in bonded warehouses in free-trade zones for just long enough to qualify for preferential tariff treatment.

The scale is stunning and the sophistication jaw-dropping.

US authorities have responded with investigations, penalties, and even new tariffs explicitly targeting trans-shipment enablers.

But the fundamental problem remains: tariff enforcement is a game of whack-a-mole against an opponent that gets smarter with every blow.

The deeper issue is that this corrodes trust in global trade statistics and the integrity of the international system itself.

If trade data is systematically distorted by evasion schemes, can anyone really know where anything comes from anymore?

Cause and Effect

The Tariff Paradox That Changed Everything

This is where logic bends. Conventional economics says that 30-percent tariffs should cripple exports. Instead, China’s exports surged. The surplus didn’t shrink; it exploded. How is this possible?

The answer lies in understanding how tariffs, when faced with a flexible, state-backed competitor, don’t stop trade—they redirect and deepen it.

The Diversion Strategy: When One Door Closes, Kick Open a Dozen

When US tariffs spiked, Chinese exporters didn’t surrender the market; they pivoted.

Shipments that might have gone to the American market were redirected to ASEAN, India, Africa, and Latin America—regions with weaker tariff regimes, stronger demand for manufacturing inputs, and rapidly urbanizing populations hungry for consumer goods.

This wasn’t panic; it was strategic reallocation.

A meaningful portion of this redirection was genuine demand growth. But the brilliance of the Chinese response was recognizing that tariff walls were asymmetric.

The US might tax Chinese goods at 60 percent, but there was nothing stopping a Chinese firm from supplying components to a Vietnamese factory that would then ship to the US.

The tariff wall suddenly had a thousand gaps, and China found every single one.

The Value-Chain Hijacking: When Tariffs Create New Business Models

Here’s where it gets sophisticated. Rather than fighting tariffs head-on, Chinese producers embedded themselves deeper into third-country supply chains.

By supplying critical intermediate goods—electronics components, machinery parts, textile inputs, solar cell precursors—to Vietnam, Malaysia, Mexico, and others, Chinese firms effectively turned partner countries into manufacturing extensions of themselves.

The endgame is elegant: a product is “made in Vietnam” for tariff purposes but is genuinely 25-50 percent Chinese value added.

When it reaches a US port, it faces Vietnamese tariffs (low) rather than Chinese tariffs (punitive).

Consumers think they’re buying American-friendly supply chains. They’re actually buying China with extra steps.

McKinsey’s research on trade geometry reveals that this phenomenon has scaled dramatically.

Vietnam’s electronics exports to America now embed roughly 25 percent Chinese value, up from about 10 percent a decade ago.

Multiply this pattern across a dozen countries and dozens of product categories, and you begin to see the architecture of tariff evasion at scale.

The Domestic Reinforcement Loop: When Policy Locks In the Surplus

Tariffs alone don’t explain the surge. They’re turbocharged by deliberate domestic policy.

Industrial policy in China channels credit and subsidies into sectors designated for global dominance—EVs, batteries, solar panels, semiconductors, advanced machinery.

Overcapacity, combined with weak household demand and deflation, creates a perverse incentive: firms maximize output and push surplus abroad rather than cut production and risk bankruptcy.

Simultaneously, self-reliance policies—the drive to localize inputs in semiconductors, machinery, chemicals, and rare-earth processing—deliberately suppress imports while freeing up export capacity.

It’s circular logic turned into systematic advantage: import less, export more, run a bigger surplus.

The result is that tariffs didn’t deter China; they accelerated these existing policy dynamics. Policymakers could tell domestic audiences that tariffs proved the necessity of self-reliance.

Firms responded by investing more in local supply chains and pushing harder into international markets. The entire system locked into a higher-export, lower-import equilibrium.

The Geographic Reorientation: When Tariffs Force a Civilizational Pivot

The most consequential effect of tariffs is not economic but geopolitical.

They’ve accelerated China’s pivot away from Western dependence toward a more diversified, non-Western trade architecture rooted in ASEAN, BRICS, the Belt and Road Initiative, and bilateral relationships with commodity-rich and manufacturing-hungry nations.

Supply-Chain Judo: How China Turned Tariffs Into Leverage

This is not temporary

Beijing is institutionalizing this through infrastructure investment, manufacturing partnerships, and financial vehicles specifically designed to be resilient to Western sanctions and tariffs.

In effect, tariffs have prompted China to build an alternative global trading system that, while still interconnected with the West, is far less dependent on Western markets and Western goodwill.

The irony is profound

The West sought to use tariffs to coerce behavioral change.

Instead, tariffs convinced Beijing that dependence on the West was a strategic vulnerability—and accelerated the very diversification that Western strategists should have feared.

Where China Is Looking Next

The New Map of Global Commerce

Ask Beijing’s trade strategists which markets matter most in a tariff-constrained world, and they’ll give you a clear answer: not the West. The future, they believe, belongs to ASEAN, South Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the BRICS bloc.

This isn’t just theory; it’s visible in trade flows, investment patterns, and diplomatic positioning.

ASEAN Ascendant: How Southeast Asia Became China’s America

ASEAN: The Center of Gravity

Southeast Asia has become China’s gravitational center.

It’s now Beijing’s largest export destination, with growth rates that make Western markets look like museum pieces. Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines are receiving Chinese goods at double-digit growth rates, spanning electronics, machinery, consumer goods, and upstream components.

But ASEAN is more than just a market; it’s an infrastructure. Vietnamese and Malaysian electronics factories run on Chinese components.

Thai manufacturing relies on Chinese machinery and inputs. Indonesian infrastructure projects use Chinese financing and equipment.

This isn’t coincidence—it’s strategy. By embedding Chinese supply chains throughout Southeast Asia, Beijing has created a region that cannot easily decouple from China without collapsing its own competitiveness.

The added bonus?

Much of what’s made in ASEAN gets exported to the US and Europe under preferential tariff treatment.

It’s beautiful from Beijing’s perspective: supply to ASEAN, let ASEAN handle Western customers, and maintain plausible deniability about origin.

The tariff wall between China and the West remains; the flow of Chinese goods continues unabated.

The India Enigma: Can Geopolitical Rivals Become Trade Partners?

India: The Rival That Can’t Be Ignored

This relationship defies easy categorization.

India and China are locked in geopolitical rivalry—border tensions, competing regional influence, divergent strategic visions.

Yet India has become one of China’s fastest-growing export markets, and bilateral trade continues to climb to record highs.

Why? Because Indian manufacturers need Chinese inputs. Indian consumers want Chinese goods.

Indian infrastructure projects use Chinese equipment.

Yes, New Delhi is attempting to build domestic alternatives through “Make in India” policies and selective protection. But the economic logic is overwhelming: China is cheaper, faster, and more capable at producing what India needs.

From Beijing’s perspective, India is both a rival to contain and an indispensable market to cultivate.

The strategy is clear: maintain export flows, deepen economic interdependence, and bet that economic ties will constrain political confrontation.

Whether that bet will pay off remains to be seen, but the numbers suggest Beijing is confident enough to maintain and even expand presence in the Indian market despite geopolitical frost.

Africa’s Debt Trap: When Trade Becomes Economic Dependence

Africa: The Frontier of Dependence

African exports are on track to exceed 200 billion dollars in 2025, and the trajectory is relentless.

The region is being flooded with Chinese machinery, construction equipment, telecoms gear, vehicles, and consumer goods—all underwritten by Beijing’s zero-tariff schemes for least-developed countries and the vast infrastructure financing machine that is the Belt and Road Initiative.

Africa represents something unique for China: a region where Beijing can simultaneously be a market player, an investor, a creditor, and an infrastructure partner.

Chinese firms win construction contracts. Chinese banks finance the projects. Chinese equipment fills the facilities. Chinese goods supply the growing consumer base. It’s a complete ecosystem of economic influence.

But it’s also creating structural vulnerabilities for African economies. As dependence on Chinese imports deepens and African debt to Chinese lenders grows, policymakers face an uncomfortable reality: their policy space is shrinking.

They want to protect local industry, but tariffs on China risk angering their largest creditor. It’s economic coercion without the drama—dependence masquerading as partnership.

Latin America’s Chinese Dream: Manufacturing, EVs, and Green Energy

Latin America: The Manufacturing Springboard

Latin America is becoming something different. Rather than just a market, it’s becoming a production base.

China is investing heavily in EV and battery manufacturing in Brazil, establishing auto-parts supply chains in Mexico that source Chinese components, and positioning itself at the heart of the region’s green industrial build-out.

The strategy is subtle but powerful.

By building manufacturing capacity near Western markets, China can claim “regional sourcing.” By controlling the supply chains feeding these factories, Beijing maintains dominance even when goods are nominally made elsewhere.

And crucially, this positions China as indispensable to Latin American industrialization at precisely the moment when the region is racing to participate in the global green-energy transition.

BRICS as Strategy: Building Tariff-Proof Trade Networks

BRICS and BRI: The Institutional Architecture

Finally, understand that ASEAN, Africa, and Latin America don’t exist in isolation for Chinese planners.

They’re nodes in a larger network: the Belt and Road Initiative and the expanded BRICS bloc.

These platforms serve multiple functions simultaneously—they lock in energy and food security, create alternative payment and settlement systems less dependent on the dollar, and institutionalize trade and investment relationships resilient to Western sanctions.

When the US slaps tariffs on China, these platforms matter because they create alternative routes for commerce, finance, and diplomatic coordination.

When Europe tightens its defenses, BRICS offers a counterweight.

The surplus doesn’t just flow in one direction; it’s being channeled through an entire alternative institutional architecture designed specifically to outlast Western pressure.

Europe’s Cold Embrace: China’s Strategy of Managed Decline

Europe: The Grudging Market

Don’t count Europe out entirely. It remains too large a market to abandon, and European consumers remain voracious for cheap goods.

Chinese exporters will continue to compete in Europe, though increasingly by accepting thinner margins, shifting some production to Central and Eastern Europe, and negotiating compromises on things like minimum price undertakings for EVs.

But the relationship is cooling. Brussels is building an economic security doctrine, strengthening trade defenses, and implementing export controls.

Europe’s pivot will be slower than America’s, but it’s real.

China’s strategy in Europe is therefore one of managed decline—preserve as much market access as possible while accepting that Europe will no longer be a growth engine.

Future Steps

The 2026 Stimulus That Might Not Work: Why Beijing’s Grand Bet Is So Risky

The Race Against the Clock

Chinese policymakers are increasingly candid about a single uncomfortable truth: you cannot run a trillion-dollar surplus forever while your domestic economy implodes.

The model is hitting walls. Household spending is too weak, property investment is collapsing, deflation is spreading, and the capacity for export-driven growth is finite. Something has to give.

The Domestic Rebalancing Bet: Can China Pivot to Consumption?

Beijing’s leadership has signaled unequivocally that strengthening domestic demand must become the top economic priority in 2026 and beyond, supported by the most aggressive fiscal stimulus in years.

The Central Economic Work Conference and Politburo communiqués are explicit: “domestic demand as the main driver” is the mantra.

The toolkit is visible and vast

A record budget deficit around 4 percent of GDP, with expectations of similar or larger deficits in 2026. Ultra-long special treasury bonds.

Consumption vouchers and trade-in subsidies for appliances and vehicles.

Targeted sectoral spending on healthcare, childcare, education, and eldercare designed to lower precautionary savings rates among Chinese households.

The ambition is massive: shift consumption’s share of GDP from about 40 percent to roughly 45 percent by 2030.

But—and this is a critical but—these measures coexist with a continued push to upgrade and expand manufacturing.

The “New Three” sectors (EVs, batteries, renewables) are still receiving preferential support.

Metals, chemicals, and advanced machinery are still being subsidized. The state is still tilting the playing field toward export-oriented sectors.

This creates an obvious tension: if you’re genuinely rebalancing toward consumption, why keep subsidizing exports?

The answer reveals Beijing’s true calculation—policymakers are hedging.

They want to shift toward consumption, but they can’t afford to lose the export growth that’s propping up employment and preventing deflation from becoming deflationary spiral.

So they’re doing both: stimulus for consumption plus continued export-sector support. The risk is that they’re trying to square a circle.

The External Backlash Is Only Getting Worse

As Chinese exports flood the world, the international environment is hardening rapidly.

The European Union is formulating an economic security doctrine that will strengthen trade defense tools, export controls, and investment screening, with China squarely in the crosshairs.

The US is unlikely to dismantle core tariffs or technology controls, even under the current ceasefire, and may actually escalate them depending on geopolitical developments.

The External Squeeze: Why Emerging Markets Are Turning Against China

More problematically for Beijing, emerging markets themselves are pushing back.

Brazil, Mexico, India, and countries across Africa and Southeast Asia are beginning to experiment with tariffs, local-content rules, and preferential procurement policies designed to protect their own industries from the Chinese onslaught.

This is deeply threatening because it closes off the escape valves—the markets where China was redirecting exports to replace lost American sales.

If ASEAN starts erecting tariff walls. If Africa demands more local content. If Latin America tightens imports. If India escalates protection. Then the surplus that seemed so sustainable suddenly becomes trapped, with nowhere to go.

The Grand Strategic Gamble: Can Beijing Thread the Needle?

For the next several years, China faces three imperatives that are increasingly difficult to reconcile.

(1) First, it must accelerate genuine domestic rebalancing toward consumption without triggering financial instability, a collapse in investment, or a property sector meltdown that becomes uncontrollable.

This is technically feasible but politically treacherous—it means the state may need to accept lower growth, tolerate some unemployment, and redistribute wealth in ways that challenge vested interests.

(2) Second, it must manage the international backlash strategically.

This means selectively absorbing concessions where necessary—agreeing to some tariff reductions, accepting some restrictions on specific sectors, localizing production in strategically important regions—while preserving enough political leverage to prevent a wholesale decoupling.

It’s a game of perpetual negotiation where China cannot afford to lose completely but also cannot afford to capitulate fully.

(3) Third, and most paradoxical, it must preserve enough export momentum to sustain growth and employment in a context of structural deflationary pressure and a fragile property sector.

If exports collapse, unemployment soars, and GDP growth stalls, the domestic rebalancing effort implodes because there’s not enough income to shift toward consumption.

This is the trilemma Beijing faces. And unlike classic economic trilemmas, there may be no elegant solution—only the painful art of minimizing losses.

The Trilemma No One Can Solve: Growth, Rebalancing, and Backlash - Dr. Bhardwaj

Threading the Needle: Beijing’s Diminishing Options

What’s Actually Going to Happen?

The most likely scenario is muddle-through.

(1) China will push stimulus hard in 2026 to boost consumption.

(2) It will continue to invest in export-oriented manufacturing while rhetorically committing to rebalancing.

(3) It will negotiate deals with key trading partners—accepting some tariffs on autos and solar, agreeing to some local-content rules—while doubling down on sectors where it has overwhelming advantages (batteries, chips, rare earths).

And it will hope that growth remains strong enough to prevent domestic instability while hoping that external demand remains resilient enough to support the surplus.

The Rebalancing Gamble: Can China Trade Export Dominance for Domestic Consumption?

But this scenario is fragile.

If domestic consumption doesn’t respond to stimulus—and evidence from Japan suggests that turning a nation toward consumption after years of export dependence is devilishly difficult—then China faces either a growth crisis or a return to relying on exports it can’t sustain externally.

If external backlash intensifies faster than expected, the surplus could shrink rapidly, leaving China without the cushion it needs domestically.

If property prices continue collapsing, financial stability could become the dominant concern, forcing Beijing to abandon or reduce stimulus just when it’s most needed.

The Clock on Rebalancing: Why China Has Only Years to Transform

The truth is that Beijing faces a clock. It has a window of perhaps three to five years to successfully rebalance before either external pressure or internal instability forces its hand.

Whether it will navigate that window successfully remains an open question.

Conclusion

After the Trillion: What the End of the Surplus Era Will Look Like

When Triumph Becomes Trap

China’s trillion-dollar trade surplus is a monument to what state-backed, ruthlessly competitive capitalism can achieve.

It demonstrates the extraordinary competitiveness and industrial depth of Chinese manufacturing, the insatiable global hunger for affordable and increasingly sophisticated technology, and the inadequacy of unilateral tariff walls in a world where supply chains span continents and nations. It is also a warning.

The surplus is simultaneously a measure of Chinese strength and a source of systemic fragility.

It confers leverage over rare earths, supply chains, and critical green technologies—Beijing can credibly threaten to withhold or redirect supplies that the world has come to depend on.

But the same surplus galvanizes coalitions determined to counter what they perceive as dumping, overcapacity, and unfair subsidies.

It accelerates both China’s integration into some regions and the speed of its decoupling from others.

A Billion Dreams, One Trillion Dollars: What Comes After the Surplus?

For Beijing, the surplus helps sustain growth in the short term but deepens external political dependence at a moment when geopolitical risk is rising sharply.

(1) How can you run an export-dependent economy when half the developed world is actively trying to reduce its reliance on your goods?

(2) How can you pursue a rising-power strategy when your surplus is destroying industries and jobs everywhere else?

(3) How can you claim peaceful rise while your surplus is destroying industries and jobs everywhere else?

The fundamental tension is unresolved and probably unresolvable

China wants to be integrated into the global economy because integration brings prosperity and technology.

But Beijing also wants strategic autonomy and the ability to pursue its interests without restraint.

The two desires are increasingly incompatible. The trillion-dollar surplus is the visible manifestation of that incompatibility working itself out.

The Rebalancing Moment: Can China Transform Before the World Pushes Back?

The Next Chapter

What happens next will shape the global economy for decades.

If Beijing genuinely rebalances toward consumption, the world might see a gradual easing of trade tensions as China’s external surplus naturally contracts.

Tariffs might begin to ease.

Emerging markets might regain policy space. The Western-led order might find a way to accommodate a China that exports less and consumes more.

The Clock on Globalization: Why 2026-2030 Will Define Everything

But if rebalancing fails—if domestic consumption doesn’t respond, if property problems explode, if deflation deepens—then China will be forced to rely even more heavily on exports to keep the economy afloat.

This would trigger a more intense external backlash, faster decoupling, and potentially a vicious cycle where both China and its trading partners feel compelled toward more aggressive protectionism.

The Surplus at the Cliff’s Edge: China’s Last Chance to Change Course

The trillion-dollar surplus of today may come to be seen as the crest of a wave—the moment when China’s export-industrial model reached its maximum expression, just before the architecture began to crack.

Alternatively, it might represent a new equilibrium, a permanent restructuring of global trade around a China that supplies most of the world with manufactured goods while buying little in return.

Either way, 2025 will be remembered as an inflection point.

The question is not whether change is coming—it is. The question is whether China can manage that change before the world forces it. And that answer will rewrite the blueprint for global commerce in the years ahead.