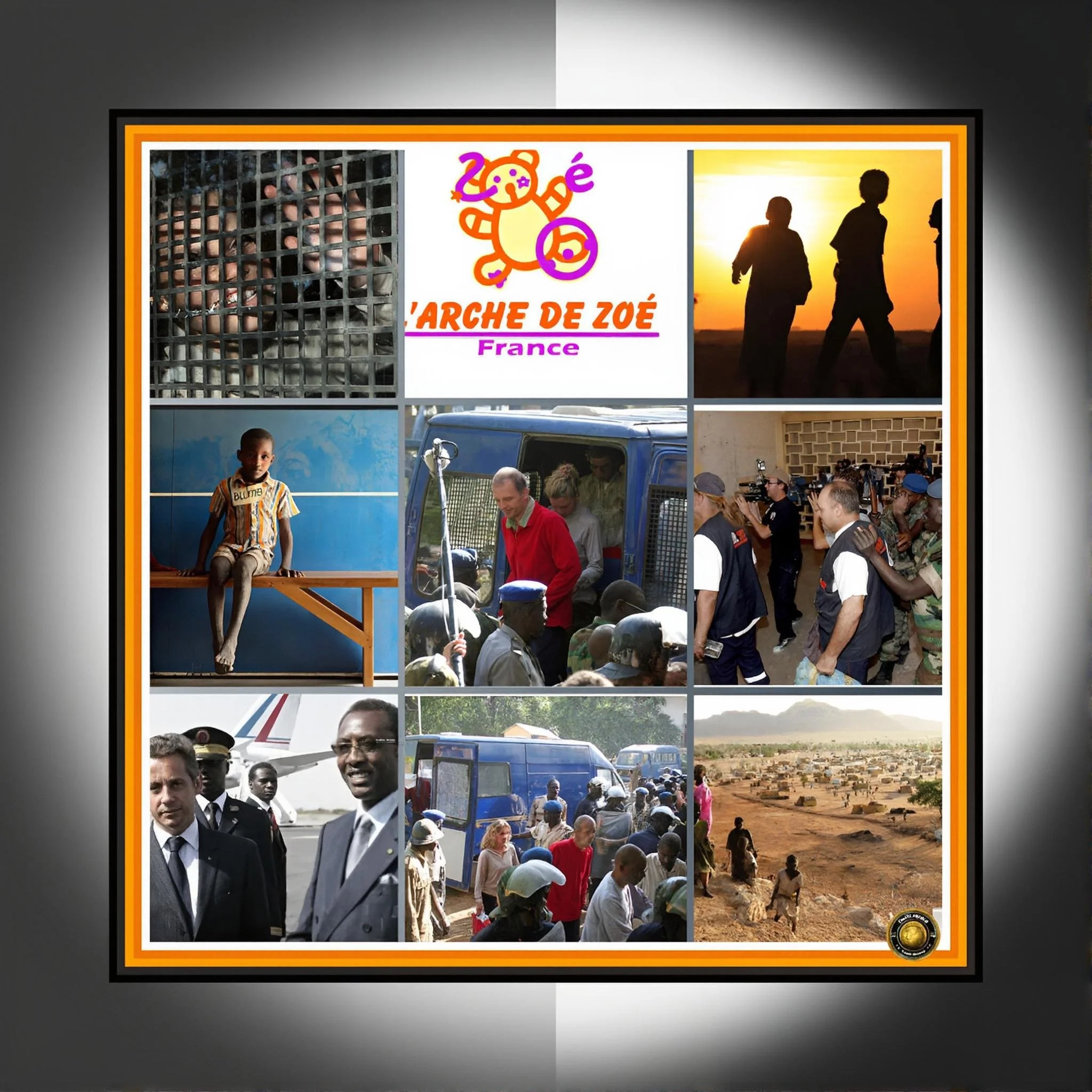

The 2007 Zoé’s Ark scandal: French Child traffickers pardoned, victims forgotten—an $8.9 million pursuit of justice that never truly happened.

Executive Summary

The 2007 Zoé’s Ark scandal represents one of the most egregious instances of child abduction masquerading as humanitarian action in recent African history.

A French charity organization, led by volunteer firefighter Eric Breteau and his partner Emily Lelouch, orchestrated an attempt to transport 103 children from Chad to France, falsely claiming they were orphans from Sudan’s conflict-ridden Darfur region.

In reality, the vast majority were Chadian nationals with living parents who had been deceived into surrendering their children through fraudulent promises of foster care placement.

The organisation even benefited from French military flights within Chad, revealing the complicity of institutional structures that should have prevented such an operation. Nearly two decades later, despite courts ordering substantial compensation, victims remain abandoned by the justice system with most having received no restitution whatsoever, as documented in a recent France 24 investigation.

Introduction

Humanitarian crises create breeding grounds for exploitation. Between genuine efforts to provide aid and the shadowy realm of trafficking and coercion lies a murky terrain where intentions blur with consequences.

The Zoé’s Ark incident exposes precisely how the language of rescue, charity and international cooperation can mask calculated deception targeting the world’s most vulnerable populations.

What began as an ostensibly noble mission to evacuate children from an active conflict zone descended into a case of attempted mass abduction, revealing fractures in child protection mechanisms across multiple nations and the inadequacy of accountability mechanisms even when perpetrators face prosecution.

The scandal unfolded with remarkable brazenness. Six members of Zoé’s Ark, including its founder, were arrested in Chad on 25 October 2007 whilst attempting to board a charter flight with 103 children. The children ranged from infants to ten-year-olds. United Nations officials who interviewed them discovered a disturbing pattern: the vast majority were not orphans from Sudan as claimed, but rather Chadian nationals, predominantly from villages in eastern Chad near the Sudanese border, with at least one living parent or guardian. According to an official list compiled by the Chadian state and consulted by France 24 investigators, only five of the 103 children involved were actually orphans. The operation exposed not merely a criminal scheme but a systemic failure of multiple institutions to detect and prevent child exploitation.

The historical context preceding this incident is essential to understanding both the perpetrators’ audacity and the international community’s culpability. Zoé’s Ark was founded in 2005 by Eric Breteau, a volunteer firefighter and former president of the French four-wheel-drive community federation. The organisation initially positioned itself as a humanitarian response to natural disasters, having been established purportedly to aid victims of the December 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

That origin story would prove deceptive. By 2006, Breteau had pivoted the organisation’s focus toward the Sudan crisis, specifically the ongoing conflict in Darfur that had created genuine refugee populations requiring protection and aid. Yet this shift represented not an expansion of legitimate humanitarian work but the laying of groundwork for an audacious scheme to traffic children across continents.

History and Background of the Case

The Darfur conflict provided both the pretext and the targeting logic for Zoé’s Ark’s operation. The conflict, which began in 2003 between the Sudanese government and rebel groups, had by 2007 created enormous civilian suffering with hundreds of thousands killed and millions displaced.

The humanitarian emergency was genuine and urgent. Into this environment stepped Breteau with a plan that he claimed would address the crisis by evacuating ten thousand orphans from Darfur to foster homes in France. The audacity of such a claim—that France would absorb thousands of African children into its child welfare system—should have triggered immediate institutional alarm.

Instead, Breteau cultivated relationships with humanitarian workers, medical personnel, and volunteer nurses, convincing them of the legitimacy of his mission through carefully constructed narratives about saving children from imminent danger.

Breteau demonstrated considerable skill in operational manipulation. He secured commitments from French families willing to serve as foster parents, collected substantial fees from prospective adoptive families (many paying thousands of euros for the opportunity to care for children they believed were Sudanese orphans), and arranged charter flights and transportation.

Critically, he obtained access to French military flights within Chad, suggesting that French state apparatus either failed in due diligence or actively cooperated without proper verification. The scale of this access points toward institutional negligence at minimum, and potentially tacit state support at maximum. French intelligence services had detected the irregular humanitarian activity, according to statements from Eric Baudet, a French official, yet the operation proceeded unimpeded until the attempted departure.

The methodology Breteau employed relied upon systematic deception of multiple constituencies. Prospective adoptive families believed they were participating in a rescue operation; humanitarian workers believed they were assisting with evacuation of conflict victims; Chadian intermediaries were allegedly compensated to identify and bring children to the operation’s base.

The children themselves, predominantly between the ages of one and ten, were too young to comprehend what was occurring. Their families were deceived into believing their children would receive medical treatment or temporary fostering, not permanent removal to Europe.

A Chadian national who served as a key facilitator later admitted that he had passed approximately sixty Chadian minors off as Sudanese Darfur refugees, falsifying documentation to substantiate the fraudulent claims.

This revelation illuminated the operation’s true character: it was not a well-intentioned initiative gone awry, but a deliberately constructed scheme built upon false documentation, bribed officials, and exploitation of vulnerable populations in a conflict zone.

Current Status and Key Developments

The 2007 incident triggered immediate arrest and prosecution across multiple jurisdictions.

Six French members of Zoé’s Ark were charged in Chad with attempted abduction and fraud on 30 October 2007, just days after their detention.

The Chadian judiciary moved swiftly, convicting all six on 26 December 2007 and sentencing them to eight years of hard labour, alongside orders to pay approximately $87,000 per child in compensation—totalling approximately $8.9 million across the 103 victims. However, the application of this sentence proved decidedly lenient.

Under an accord negotiated between the Chadian and French governments at the sidelines of an EU-Africa summit in Portugal, the six were repatriated to France instead of serving their sentences in a Chadian facility.

In March 2008, Chadian President Idriss Deby pardoned all six members, effectively erasing their criminal convictions in the nation where the crime had occurred.

The French judiciary subsequently pursued its own prosecution. The Paris trial opened in December 2012 and concluded in February 2013, with Eric Breteau and Emily Lelouch convicted and sentenced to two years in prison for fraud and acting as illegal intermediaries in adoption proceedings.

The court also convicted four other members to suspended sentences ranging from six months to one year.

Critically, these sentences themselves proved suspended, indicating they would not serve imprisonment provided they violated no laws for a defined period. An appeal in 2014 further reduced their sentences to purely suspended terms. By 2014, all six key perpetrators had either been pardoned or released without serving meaningful prison time in any jurisdiction.

The most devastating consequence for victims emerged in the gap between legal judgements and actual compensation distribution.

The Chadian state deposited 562 million CFA francs (approximately $850,000) in 2009 as a compensation fund for child victims. Yet approximately nine years later, when France 24 investigators researched the matter, they discovered that none of the approximately sixty children remaining in contact with each other had received any compensation whatsoever.

This revelation emerges as perhaps the cruelest aspect of the entire scandal: a court system had ordered compensation; funds had been allocated; yet the victims, now adults traumatised by their childhood experience, remained without recourse to justice or reparation.

The January 2026 France 24 “Revisited” documentary brings this unresolved case into contemporary focus, highlighting that eighteen years after the attempted abduction, most victims continue seeking both acknowledgement and compensation.

The documentary features Adam, one of the children (now 23 years old), who was five years old when Zoé’s Ark attempted to remove him from Chad. Through his testimony and that of other victims, the investigation reveals the psychological toll of having been treated as commodities in a criminal scheme, placed under protective custody in Chad whilst awaiting resolution that never materialised, and subsequently abandoned by both the justice systems and the international humanitarian apparatus that had failed to protect them.

Key Developments and Structural Failures

Several critical junctures reveal systematic failures in child protection and international accountability.

First, the operation’s ability to secure French military flight access without triggering proper vetting procedures indicates that French state institutions failed to implement basic due diligence before providing material support to an NGO with suspicious claims and insufficient documentation. The military flights were not incidental logistical support but rather direct facilitation of a criminal enterprise.

Second, the operation proceeded despite detection by French intelligence services. According to official statements, French intelligence had identified irregular humanitarian activity associated with Zoé’s Ark, yet Eric Breteau and Emily Lelouch were summoned to the ministry for questioning without meaningful consequence or interdiction. This suggests that knowledge of suspicious activity did not translate into preventive action.

Third, the Chadian government’s decision to pardon the six members—whilst seemingly merciful or politically expedient—essentially erased accountability in the jurisdiction where the crime occurred. Victims were denied closure in their home legal system; perpetrators avoided serving sentences; and the message sent to potential traffickers was one of impunity.

Fourth, the compensation fund established in 2009 became a de facto confiscation of victims’ rights.

Although $850,000 was allocated, the mechanism for distributing these funds to victims remained opaque, inaccessible, and non-functional. This created a situation where the Chadian state could claim to have addressed victims’ needs whilst actual victims received nothing.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis

The Zoé’s Ark scandal did not emerge from spontaneous criminality but rather from a confluence of structural factors that enabled exploitation. Understanding these causal mechanisms illuminates how similar operations might recur in the future.

Humanitarian Emergency Exploitation constitutes the foundational cause. The genuine Darfur crisis created both desperate populations seeking rescue and international attention focused on the region.

Breteau capitalized upon this attention by framing his operation as an extension of legitimate humanitarian work. This represents a classic “protective mimicry” strategy wherein criminal activity mimics legitimate structures to evade detection. The presence of genuine humanitarian need obscured the illegitimate operation unfolding within its shadow.

Second, institutional deficiencies in child protection verification enabled the scheme. Child welfare systems in France, Chad, and internationally did not possess adequate mechanisms to verify the provenance and family status of children before placement in adoption pipelines.

The absence of comprehensive identity documentation systems in conflict zones provided convenient cover for trafficking. Families in eastern Chad could not produce birth certificates or formal adoption documents that would have been required in a properly functioning child protection system. This gap between child welfare regulations in developed nations and documentation capacity in developing nations created a vulnerability that Breteau exploited.

Third, financial incentives aligned with institutional negligence. French prospective adoptive families paid substantial sums for the opportunity to participate in Zoé’s Ark’s programs. These fees created revenue streams that incentivized operational continuation. Simultaneously, humanitarian workers were drawn into the operation partly through appeals to their values but also partly through the prestige and social capital associated with rescue operations. These individuals became not merely witnesses but unwitting participants in the scheme.

Fourth, regulatory gaps in NGO oversight allowed Zoé’s Ark to operate with minimal legitimate accountability. The organisation was registered with French authorities as a legitimate non-governmental organisation, suggesting that registration processes failed to flag the organisation’s activities or subsequent evolution from tsunami relief to African child evacuation as concerning developments requiring enhanced scrutiny.

Fifth, the geopolitical interests of France in Chad created diplomatic constraints on prosecution. France maintained significant military, economic, and political interests in Chad. The rapid negotiation of an accord allowing six convicted individuals to be repatriated rather than serve sentences in a Chadian facility reflected this power asymmetry. A weaker nation could not maintain prosecutorial independence when a former colonial power exerted political pressure to reduce accountability.

Sixth, the absence of robust international child trafficking frameworks in 2007 meant that the incident, though egregious, did not trigger international criminal procedures available today.

Chad was not a signatory to the 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, eliminating a potential avenue for enforcement across borders. The framework for prosecuting international child trafficking was substantially less developed than mechanisms that emerged in subsequent years.

Future Trajectory and Evolving Justice Claims

The documentary evidence presented by France 24 in January 2026 suggests that the Zoé’s Ark case remains unresolved in the eyes of victims, despite the completion of multiple criminal proceedings.

The persistence of victims’ claims into the third decade following the incident reflects several dynamics. First, the psychological trauma resulting from childhood abduction and subsequent abandonment by the international justice system creates enduring grievance that does not fade through mere passage of time.

The children, now adults, carry the scars of having been treated as commodities, of having their families deceived, of having been subjected to attempted transplantation to a foreign nation against their will or their families’ informed consent.

Second, the non-distribution of compensation funds creates ongoing injustice. The existence of an allocated compensation fund that remains inaccessible to victims transforms institutional neglect into active victimization.

The Chadian state allocated the funds in 2009 yet apparently took no steps to locate victims or distribute compensation. This suggests either deliberate obstruction or such profound institutional incapacity that the commitment remained merely symbolic.

Third, the international publicity generated by France 24’s investigation in 2026 re-centers the case in public consciousness and potentially creates political pressure for resolution. Eighteen years is a substantial period, but it is not beyond the reach of contemporary justice systems to address historical grievances, particularly when institutional neglect remains the primary barrier rather than evidentiary insufficiency.

The future trajectory will likely depend upon several factors. If the documentary generates political pressure within France or Chad, renewed negotiation over compensation distribution might occur. If survivors organise collectively and pursue civil litigation in French courts against both the state (for military flight provision) and the remaining institutional actors who facilitated the operation, new legal pathways might emerge.

International advocacy organisations focused on trafficking and child rights could amplify the case and create external pressure for accountability. Alternatively, if institutional inertia continues, the case might fade again from public consciousness, leaving victims with legal judgements but no material remedies.

Conclusion

The Zoé’s Ark scandal represents a failure of multiple institutions to protect vulnerable children from exploitation by actors who strategically exploited humanitarian rhetoric and institutional gaps.

The incident occurred not as an anomalous criminal act but as a predictable consequence of structural vulnerabilities in international child protection systems, inadequate oversight of NGO activities in conflict zones, and the persistent power asymmetries that allow wealthy nations to constrain the prosecutorial independence of weaker nations.

Nearly two decades have elapsed since the attempted abduction. Multiple prosecutions have concluded. Perpetrators have been pardoned or released without serving substantial sentences.

A compensation fund has been established. Yet the children, now adults, remain without meaningful access to justice or material remedy. This enduring injustice reflects not a failure of law or evidence but a failure of institutional will to follow through on the commitments that courts have made. The January 2026 France 24 investigation resurrects this case precisely to expose this gap between legal findings and practical implementation.

The scandal carries implications extending far beyond the 103 individuals affected. It illuminates how humanitarian crises create vulnerability to exploitation, how institutional neglect enables trafficking, how power asymmetries constrain accountability, and how even when legal systems identify wrongdoing and order remedies, the failure to implement those orders leaves victims abandoned.

Until compensation funds are distributed, until psychological support services are provided, until institutional reforms prevent recurrence, the Zoé’s Ark case remains unresolved—a monument to the gap between justice and its practical realisation.