Kurdish Self-Determination Imperilled by Centralization: A Critical Analysis of the SDF-Syrian Government Integration Agreement and Regional Power Dynamics

Executive Summary

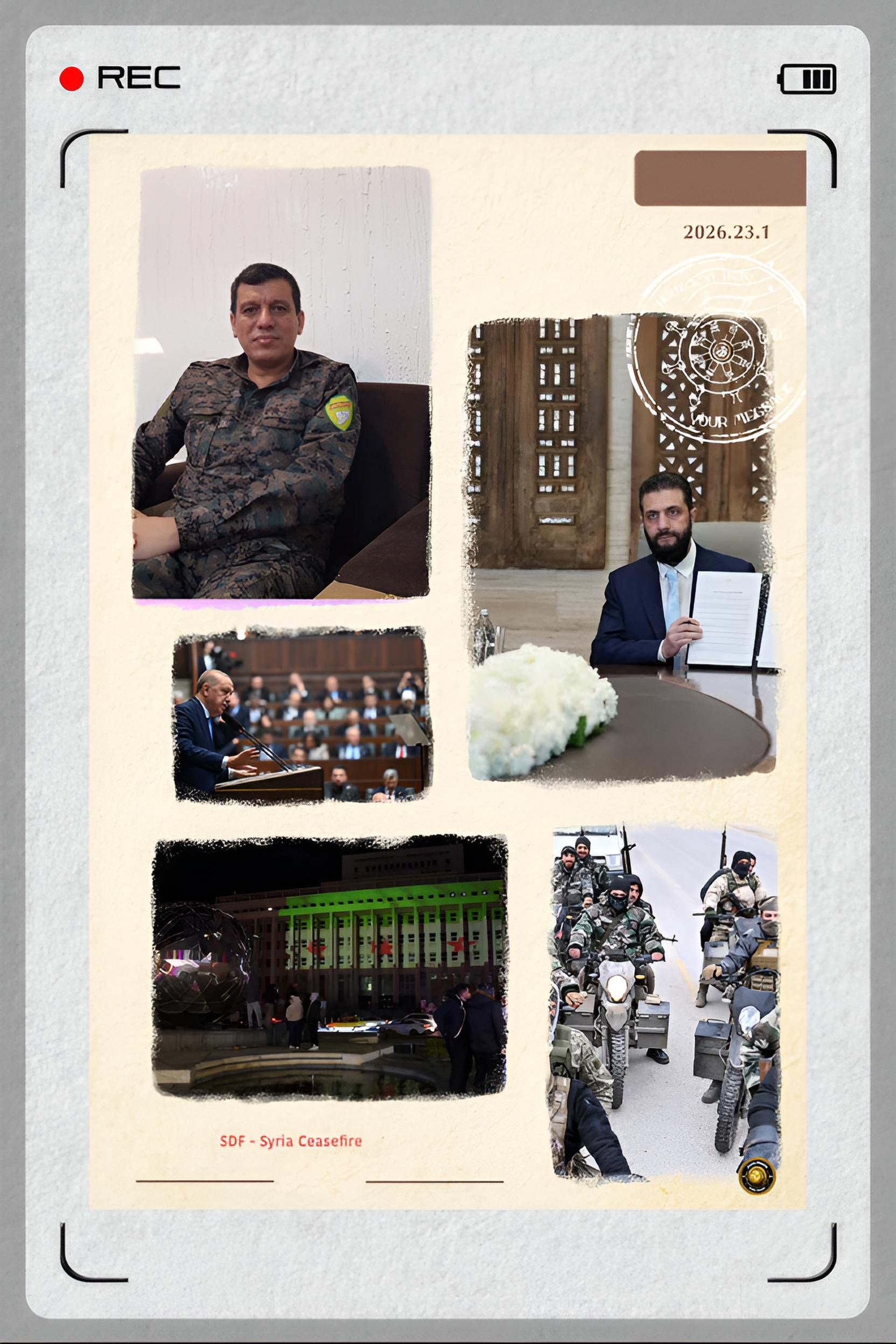

The agreement reached between the Syrian government under President Ahmad al-Sharaa and the Syrian Democratic Forces on January 30, 2026, represents a fundamental capitulation of Kurdish aspirations for autonomous governance, effecting what many analysts characterize as the strategic dismantling of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).

The accord stipulates the subordination of the Syrian Democratic Forces' 50,000-plus fighters to individual integration within Syrian military brigades, the transfer of all oil and gas resources—representing the predominance of Syria's hydrocarbon wealth—to central government control, and the absorption of Kurdish-led civil institutions into state structures, thereby effecting the dissolution of 14 years of de facto self-governance established since 2012.

FAF analysis demonstrates that the agreement constitutes a profound betrayal of Kurdish political aspirations, accomplished through 3 mechanisms: the withdrawal of United States military support upon which Kurdish security depended, Turkish pressure and military assistance to Damascus forces, and the international legitimization of centralized state authority over ethnic self-determination principles.

The integration process simultaneously fails to protect Kurdish institutional autonomy or provide credible guarantees regarding the utilization of oil revenues for Kurdish community development.

Furthermore, the agreement's construction perpetuates the risk of sectarian violence and political marginalization that characterized pre-2011 Syrian governance, potentially engendering instability superior to that which would result from negotiated federal arrangements respecting Kurdish administrative capacity and territorial integrity.

Introduction and Historical Context

The Genesis of Kurdish Autonomy and Its Structural Sustainability

The emergence of Kurdish autonomous governance in Syria between 2012 and 2015 occurred within a singular historical configuration wherein the collapse of central state authority—consequent to the Syrian civil war initiated in 2011—generated a power vacuum that Kurdish parties, operating under the Democratic Union Party aegis and subsequently the Syrian Democratic Forces coalition, exploited to establish de facto self-governance structures.

This autonomous administration, denominated Rojava in popular discourse and formally the AANES, encompassed approximately 30% of Syrian territory at its zenith, controlling vast agricultural regions along the Euphrates River and, critically, the overwhelming preponderance of Syria's remaining oil and gas reserves concentrated in Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa provinces.

The territorial configuration of the autonomous region reflected long-standing Kurdish demographic distributions, with predominantly Kurdish populations concentrated in 3 discontinuous zones: Afrin in the northwest, Kobani in the north, and Rojava proper in the northeast stretching from Hasaka through Qamishli.

Kurdish autonomy within these territories acquired a material basis in 2 primary mechanisms: the development of autonomous civil institutions including educational systems conducting instruction in the Kurdish language, local judiciary structures, police forces, and municipal governance councils; and the deployment of approximately 50,000 fighters organized under the SDF umbrella, representing the most coherent and disciplined military force in Syria exterior to the Syrian government proper.

The political and ideological foundations of the autonomous administration reflected a theoretical commitment to democratic confederalism, a governance model predicated upon decentralized governance through local councils rather than hierarchical state authority.

In practice, this governance framework generated measurable institutional continuity and local legitimacy, particularly in predominantly Kurdish regions where the administration functioned as the primary provider of public services, security, dispute resolution, and educational provision. The autonomous administration maintained trade relationships with both Turkish-controlled territories to the north and Syrian government-controlled regions to the west, generating economic activity that, while constrained relative to pre-conflict levels, sustained basic social functionality.

The structural vulnerability of Kurdish autonomy derived not from internal institutional weakness but rather from geopolitical contingency: the autonomy's sustainability depended upon 3 external conditions that proved temporally contingent.

First, continued United States military presence and support, which provided deterrent effect against both Syrian government military action and Turkish military operations against Kurdish territories.

Second, the fragmentation of Syrian central authority consequent to the Assad regime's loss of territorial control, which rendered military reconquest of the northeast logistically infeasible.

Third, the acceptance by regional powers—particularly Turkey—of Kurdish autonomy as tolerable given its perceived utility in counterbalancing more radical Islamist forces and preventing territory's control by al-Qaeda-linked organizations.

The Categorical Transformation

From Negotiated Autonomy to Forced Integration

The November 2024 fall of Bashar al-Assad and the subsequent rise of Ahmad al-Sharaa, an Islamist leader of the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham faction, fundamentally altered this equilibrium.

Al-Sharaa articulated immediately upon assumption of power a doctrine predicated upon comprehensive Syrian territorial unification under central government authority, rejecting explicitly any federal arrangements or decentralized governance structures that would institutionalize Kurdish autonomy.

Al-Sharaa's position rested upon 3 foundational premises: the principle of territorial sovereignty dictated that no subnational entity could exercise autonomous authority; the notion that Kurdish aspirations for self-determination constituted a national security threat analogous to separatism; and the conviction that Syria's oil and gas resources represented state property necessary for national reconstruction.

Simultaneous with al-Sharaa's articulation of these principles, the United States government, which had maintained approximately 900 troops in northeastern Syria providing military support to the SDF's counter-ISIS operations, signaled in January 2026 a strategic reorientation.

American officials, including US Special Envoy Tom Barr, explicitly declared that the "original purpose of partnership with SDF, the primary anti-ISIS force in Syria, has largely expired," and that "the greatest opportunity for Syria" resided in the transition under al-Sharaa's administration.

This declaration effectively terminated the security guarantee that had underlain Kurdish autonomous viability. With American military support withdrawn, the SDF confronted the prospect of defending Kurdish territories against both Syrian government forces and Turkish military support supplied to those forces without external deterrent effect.

Turkey, under the governance of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan, pursued simultaneously a military and diplomatic campaign to ensure the eradication of Kurdish autonomy.

Turkish officials reiterated repeatedly that Ankara would not tolerate "any separatist structure along our southern borders" and characterized the Syrian Democratic Forces as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers' Party, which Turkey designates as a terrorist organization.

Turkey proceeded to provide military support and coordination with Syrian government forces conducting operations against SDF-controlled territories. Turkish drones conducted strikes against SDF positions, while Turkish military intelligence provided operational coordination assisting Syrian forces in reconquering territories that the SDF had controlled.

The SDF, faced with the simultaneous withdrawal of American support and Turkish military pressure coupled with Syrian government military offensive capabilities, confronted a categorical military imbalance.

The organization demanded, during negotiations with al-Sharaa's government, conditions it characterized as essential for accepting integration: 30% representation across all government branches including 28 ambassadorships; the creation of 3 Kurdish-majority governorates with elected Kurdish governors; retention of 25-30% of oil revenues for autonomous Kurdish development; and codification of Kurdish linguistic and cultural rights within the interim constitution.

The Syrian government categorically rejected these demands, characterizing them as "suicidal" for al-Sharaa's political position and incompatible with the principle of unified state authority.

Faced with military overwhelming force, the SDF capitulated.

The January 30, 2026 agreement stipulated: individual integration of SDF fighters into Syrian military brigades rather than preservation of cohesive SDF units; the transfer of all oil and gas revenues to central government control; the subordination of Kurdish-led civil institutions to state authority; the transfer of IS detention camps and prisoner facilities to Damascus; and the integration of Kurdish administrative apparatus into central government structures whilst ostensibly preserving "civil and educational rights for the Kurdish populace."

The Illusory Character of Promised Kurdish Protections

The agreement's language regarding Kurdish cultural and linguistic rights must be situated within the context of the preceding 50 years of Syrian state policy toward Kurdish populations.

Between 1962 and 2011, the Assad regime systematized the marginalization of Kurdish identity through mechanisms including the denial of citizenship rights to over 100,000 Kurds, the prohibition of Kurdish language instruction, the suppression of Kurdish cultural expression, and the deliberate settlement of Arab populations in predominantly Kurdish regions as a mechanism of demographic alteration.

Al-Sharaa's January 17 presidential decree, which nominally recognized Kurdish as a national language and declared Nowruz, the Kurdish New Year, a national holiday, represented the first formal state recognition of Kurdish cultural identity. Yet this decree possessed no constitutional binding force and functioned primarily as a tactical maneuver designed to facilitate the SDF's acceptance of integration.

The agreement stipulates that Kurdish administrative officials may submit candidates for "high-ranking military, security, and civilian positions within the central state structure" to ensure "national partnership."

However, this language provides no institutional guarantee that Kurds will exercise meaningful influence over policy affecting Kurdish-majority regions. Rather, the formulation permits the central government to accept or reject Kurdish candidates based upon political criteria determined unilaterally by Damascus.

Moreover, the agreement requires the SDF to "remove all non-Syrian leaders and non-Syrian members of the Kurdistan Workers' Party from its ranks," a provision that effectively subordinates the SDF's organizational autonomy to state security apparatus scrutiny and empowers Damascus to utilize counter-terrorism justifications for eliminating SDF political leadership.

The agreement's stipulation regarding "civil and educational rights for the Kurdish populace" similarly lacks enforcement mechanisms or constitutional grounding. The provision does not guarantee Kurdish-language education, Kurdish cultural autonomy, or Kurdish representation in civil service appointments.

Rather, it establishes rights contingent upon central government forbearance, which historical precedent suggests offers minimal protection. The guarantee of "return of displaced persons to their areas" addresses the demographic alteration inflicted by Turkish military operations in Afrin and the subsequent settlement of anti-Kurdish Syrian factions, yet provides no mechanism for reversing the settlement patterns established or compensating for property losses sustained.

The Oil Revenue Question and Economic Marginalization

The transfer of all oil and gas resources to central government control represents the most consequential betrayal of Kurdish interests embedded within the integration agreement. The northeast Syrian oil fields produce approximately 150,000 to 200,000 barrels per day, constituting the preponderance of Syria's remaining hydrocarbon wealth.

Before the Syrian civil war, oil revenues constituted a substantial proportion of state income. Following the destruction of infrastructure and the economic collapse consequent to 14 years of conflict, oil and gas revenues represent the primary mechanism through which Syria can finance reconstruction and generate resources for state apparatus functionality.

The SDF initially demanded that 25-30% of oil revenues be retained for Kurdish-administered autonomous development, a demand rooted in the principle that the resource extraction occurred from predominantly Kurdish territories and that revenues should finance development and service provision in those territories.

The Syrian government rejected this demand, insisting upon complete central control and sole authority to determine resource allocation. The final agreement stipulates no provisions for special revenue-sharing arrangements with Kurdish regions. Rather, all hydrocarbon resources are transferred to "state control," with implicit understanding that Damascus will determine resource allocation through centralized budgetary processes in which Kurdish representation, if existent, will constitute a minority voice.

This outcome perpetuates the structural economic marginalization that characterized pre-civil-war Syria. Throughout the Assad era and preceding decades, the northeast—despite possessing significant oil wealth and agricultural productivity—received proportionally minimal state investment in infrastructure, healthcare, and educational services.

Kurdish regions were systematically underfunded relative to regime-controlled areas around Damascus and in the Alawite coastal region. The integration agreement, by transferring oil revenues to central control without constitutionalizing resource-sharing arrangements, creates institutional conditions for the perpetuation of this marginalization.

Furthermore, the transfer of oil resources to a government characterized by widespread corruption and by the concentration of power in Islamist-aligned factions creates risk that revenues will be misappropriated rather than deployed for national reconstruction.

International observers have documented that corruption within Syrian state institutions—particularly the military and security agencies—remains endemic. The likelihood that oil revenues derived from Kurdish territories will be deployed for Kurdish community benefit appears minimal given the absence of constitutional guarantees and the historical patterns of Kurdish marginalization.

The Syrian National Army and the Foreign Militant Dimension

The user's concern regarding the composition of the Syrian National Army and the presence of foreign insurgents within its ranks merits detailed examination. The SNA, which functions as Turkey's primary proxy force in northern Syria, does indeed comprise heterogeneous factions with diverse ideological orientations and foreign fighter compositions.

The organization includes former Free Syrian Army units, nationalist Islamist groups, Turkmen militias, and Salafi-jihadist contingents. Approximately 80,000 fighters organized under the SNA umbrella operate under nominal control of the Syrian Interim Government's Ministry of Defence, though practical command authority resides with Turkish military intelligence.

A significant proportion of SNA fighters are foreigners rather than Syrian nationals.

These include Uyghur fighters originating from Xinjiang who previously fought under the banner of the Turkistan Islamic Party, Chechen fighters organized under groups denominated Ajnad al-Qawqaz and other jihadist formations, and fighters from Balkan states organized under the so-called Balkan Battalion.

Additionally, elements of al-Qaeda-linked organizations including Hurras al-Din maintained presence within SNA-controlled territories until their nominal dissolution in early 2025.

Contrast this composition with the SDF, which, while containing approximately 50,000 fighters, comprises predominantly local populations—approximately 40% Kurdish and 60% Arab.

The SDF's force composition reflects local recruitment and local constituencies, whereas the SNA represents a collection of foreign contingents, Turkish proxies, and ideologically diverse groups united primarily by Turkish financial support and Turkish strategic interests rather than by shared commitment to Syrian reconstruction or inclusive governance.

The integration agreement privileges the centralization of authority under al-Sharaa and the SNA, thereby effectively subordinating the more locally-representative SDF to the more foreign-dominated and Turkish-aligned SNA.

This represents an inversion of principles predicated upon local legitimacy and democratic governance. The SDF's local rooting and predominantly local fighter composition suggests substantially greater legitimacy for governance within predominantly Kurdish regions than does the SNA's composition dominated by foreign fighters and Turkish-aligned Turkmen elements.

Turkish Ambitions and the Structural Impediments to Kurdish Self-Determination

Turkey's hostility to Kurdish autonomy in Syria extends beyond mere security concerns and reflects instead a strategic commitment to preventing the consolidation of Kurdish political power in any neighboring territory.

Turkish officials characterize the Syrian Democratic Forces as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers' Party, a designation reflecting the SDF's ideological commitments to democratic confederalism and to the personal authority of Abdullah Öcalan, the incarcerated PKK leader.

Turkey's opposition to Kurdish autonomy is predicated fundamentally upon the conviction that successful Kurdish self-governance in Syria would provide an ideological model and a potential base for mobilization of Turkey's own substantial Kurdish population.

Turkey's pursuit of Kurdish demilitarization and forced integration into central authority under al-Sharaa reflects a doctrine that may be characterized as "victory without compromise." Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan has explicitly demanded the SDF's unconditional surrender and complete subordination to Damascus.

The Turkish model applied historically within Turkish territory involves the militaristic suppression of Kurdish political organization combined with cultural assimilation pressures. Fidan has indicated willingness to employ military force against the SDF if integration negotiations do not proceed to Turkish satisfaction, and Turkish drones have already conducted strikes against SDF positions during January 2026 clashes.

This Turkish approach creates a fundamental structural impediment to the negotiation of inclusive federal arrangements that might accommodate both Kurdish self-governance and central state authority.

Turkey's veto power over any Kurdish political autonomy—exercised through military threat and through coordination with al-Sharaa's government—renders impossible the negotiation of genuine power-sharing arrangements.

Any genuine Kurdish autonomy would require Turkish acquiescence, which appears unattainable given Turkey's strategic perception of Kurdish independence as threatening to Turkish territorial integrity and to Turkish state security.

Comparative Analysis

The Iraq Precedent and Alternative Governance Models

The integration agreement's risks can be illuminated through comparative analysis with Iraq's post-2003 experience.

Following the American invasion and the fall of Saddam Hussein's regime in 2003, Iraq established a federal structure explicitly protecting Kurdish autonomy through constitutional mechanisms.

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq emerged as the most stable and prosperous region within Iraq, characterized by functioning civil institutions, absence of sectarian violence, and relative economic development.

The federal structure, despite its limitations and despite tensions between Baghdad and the Kurdish region regarding resource distribution and disputed territories, prevented the militaristic reassertion of central control over Kurdish areas.

Syria's integration agreement constitutes a categorical rejection of the federal model evidenced in Iraq. Instead of constitutional protections for Kurdish autonomy, the agreement establishes individual integration of SDF fighters into central military structures and subordination of Kurdish institutions to state authority.

This approach maximizes risk of the sectarian violence and political marginalization that characterized pre-2011 Assad-era governance and that precipitated the original Syrian civil conflict.

The risk of descent into Iraqi-style sectarian violence exists particularly given the heterogeneous composition of the new Syrian state. Syria contains substantial Alawite, Druze, Sunni, and Kurdish populations, along with smaller populations of Circassians, Turkmen, and other groups.

The concentration of all authority in a centralized state structure controlled by an Islamist faction aligned with Sunni interests creates precisely the structural conditions that generated Sunni-Alawite conflict during the Assad era. Marginalized Kurdish and Druze populations, lacking institutional protections for minority rights, become vulnerable to both majoritarian political pressures and to security force repression.

Future Scenarios and the Risk of Renewed Instability

Multiple future scenarios appear plausible given the integration agreement's current architecture. In the optimistic scenario, al-Sharaa's government demonstrates unexpected restraint in exercising authority over Kurdish regions, permits genuine local autonomy despite the absence of constitutional grounding, and allocates oil revenues equitably toward Kurdish community development.

This scenario, however, requires assumptions contradicted by historical precedent. The Assad regime's systematic marginalization of Kurdish regions, combined with the absence of constitutional guarantees and the concentration of discretionary authority in al-Sharaa's hands, renders this scenario improbable.

A more plausible scenario involves the gradual reassertion of central control over Kurdish territories, the suppression of Kurdish cultural and linguistic expression despite nominally recognizing Kurdish language rights, and the utilization of state security apparatus authority to eliminate Kurdish political leadership.

In this scenario, the security guarantees nominally provided to Kurds through the integration agreement prove illusory, and the political situation replicates pre-2011 patterns of Kurdish marginalization. The consequence would be renewed Kurdish resistance and potential return to armed conflict.

The most concerning scenario involves the complete descent of the Syrian state into sectarian fragmentation and renewed civil conflict.

The integration of the SDF into state structures whilst preserving Turkish-aligned SNA factions as distinct entities creates structural incentives for renewed conflict. If marginal Kurdish or Druze communities perceive central authority as exercising discriminatory repression, they retain the option of armed resistance.

The militarization of Syrian society and the abundance of weapons distributed among various factions creates conditions wherein conflicts rapidly escalate into communal violence.

Recommendations for Preventing Descent into Renewed Instability

The international community, and particularly the United States, must recognize that the current integration agreement creates substantial risk of renewed instability rather than genuine stabilization.

The optimal approach would involve explicit commitments to Kurdish self-governance within a federal framework that preserves central state authority over defense and foreign policy while establishing genuine autonomy for Kurdish-majority regions regarding internal administration, education, and cultural policy. The Iraqi precedent demonstrates the feasibility of such arrangements.

Alternatively, if a unified Syrian state is deemed preferable, the constitutional framework must incorporate explicit protections for minority rights, proportional representation of Kurdish populations in state institutions, and mechanisms for revenue-sharing that allocate resources derived from Kurdish territories for Kurdish development.

Such provisions require international enforcement mechanisms and international monitoring, as the historical record demonstrates that voluntaristic commitments from centralized governments to minority protection prove unreliable.

The United States should condition its support for al-Sharaa's government upon demonstrable commitment to inclusive governance and minority protection.

The current American posture, wherein the US supports al-Sharaa whilst abandoning the SDF, signals indifference to democratic governance and minority rights. This American approach generates legitimate grievances among Kurdish populations and undermines American credibility as an advocate for human rights and democratic principles.

Conclusion

The integration agreement between the Syrian government and the SDF represents a profound capitulation of Kurdish aspirations for autonomous self-governance and for the preservation of the institutional achievements accumulated during 14 years of autonomous administration.

The agreement transfers all oil revenues to central control, subordinates Kurdish military forces to individual integration within state structures, and subjects Kurdish civil institutions to state authority, whilst providing nominal and unenforceable guarantees regarding Kurdish cultural and linguistic rights. This configuration replicates the structural conditions that precipitated the original Syrian civil conflict through Kurdish and other minority marginalization.

The international community should recognize that genuine Syrian stabilization requires inclusive governance structures respecting Kurdish self-determination and providing constitutional protections for minority populations.

The current integration agreement, lacking such protections and concentrating authority in an Islamist-aligned government hostile to Kurdish autonomy, creates high probability of renewed instability. The alternative of negotiated federalism, exemplified by the Iraqi model, represents a superior path toward both Kurdish aspirations for self-governance and toward genuine stabilization of the Syrian state.

The abdication of American support for Kurdish forces and the acquiescence to Turkish pressure for Kurdish elimination demonstrates the triumph of realpolitik over democratic principles, with consequences that will likely generate instability superior to that which federal arrangements would produce.