Summary

What Happened: A Simple Explanation

Imagine you live in a house that gets taken over by a new owner. For over ten years, you managed that house yourself, paid the bills from oil money, and made your own decisions. The government was weak and far away, so you had the freedom to run things your way. You were also critical to a powerful friend in another country—they supported you militarily and protected you.

But in January 2026, everything changed. The new owner of the house decided they wanted control back. They had a powerful ally, Turkey, pushing them from the side, telling them they needed to take back control immediately. Your powerful friend—the United States—looked at the situation and decided to support the new owner rather than protect you.

The military fight lasted just two weeks. By January 18, 2026, you had lost almost everything. You gave up control of the oil fields that paid your bills, the houses you lived in, and the security forces you commanded. You were forced to integrate your soldiers as individuals into the government army rather than keeping them as your own. You lost the ability to make your own decisions.

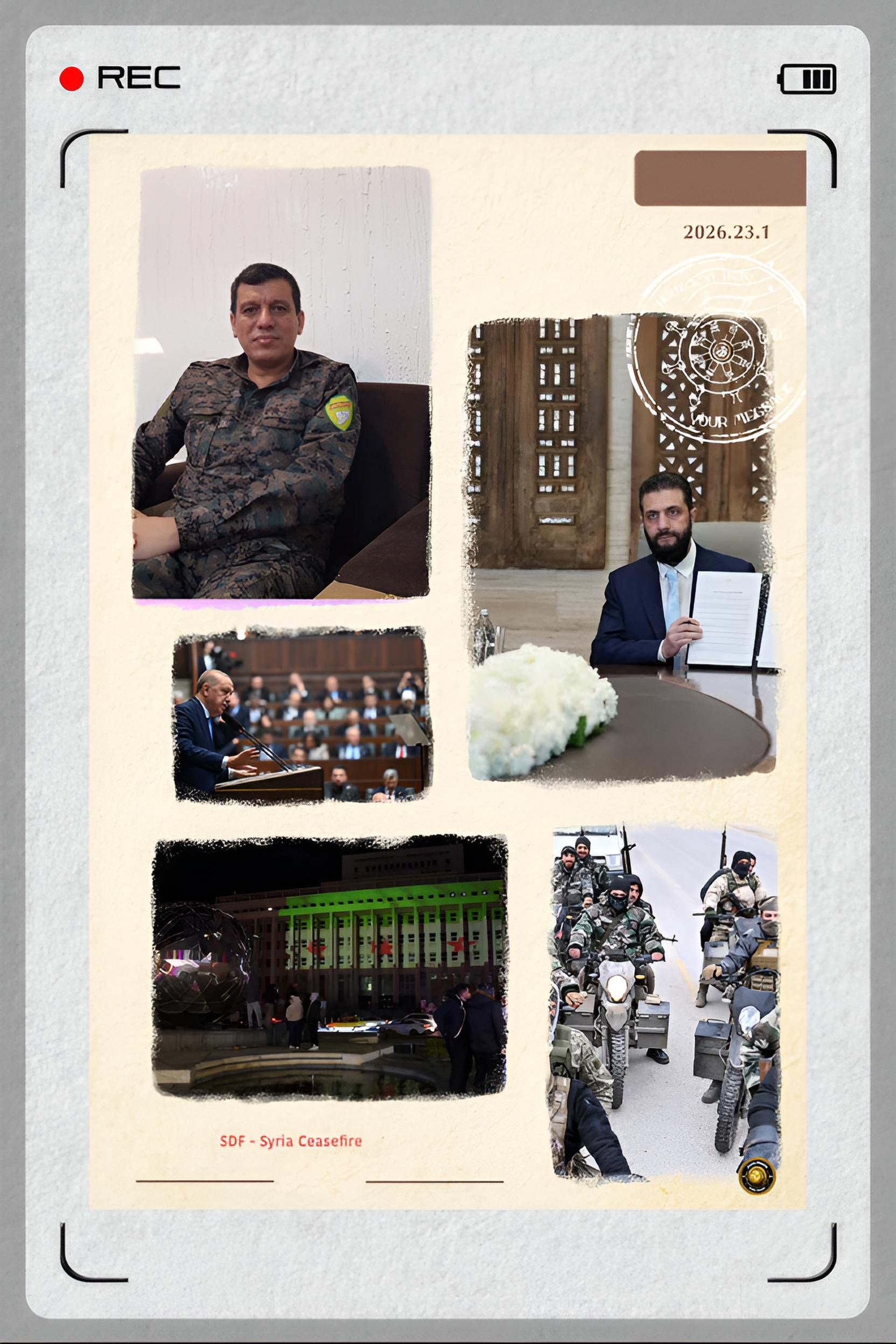

This is what happened to the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-led military group that controlled a significant area of northeastern Syria.

The Historical Background

How the Kurds Got Control

To understand what happened in January 2026, we need to go back to 2012. Syria's government collapsed into civil war. The army fell apart. Suddenly, there was chaos and no authority in charge of the northeastern part of the country.

The Kurdish people, who had lived in that area for centuries, filled the power vacuum. They created their own government called DAANES. They ran schools, hospitals, police forces, and security operations. They organized democratic councils. For many people around the world, this seemed like a good experiment in self-governance. Kurdish newspapers printed stories about a new kind of democracy taking root in the Middle East.

But there was a problem. DAANES had an even more powerful friend than most countries. From 2014 to 2019, the Islamic State—a terrorist group that controlled vast areas of Iraq and Syria—was expanding. The U.S. military decided that the Kurdish forces were the only reliable ground troops who could defeat ISIS. So Washington gave the Kurds weapons, air support, and money. U.S. soldiers worked alongside Kurdish fighters.

By 2019, ISIS was militarily defeated. The Kurds had done most of the fighting. They had lost thousands of their own people. They had also captured thousands of ISIS fighters and were running massive prison camps and detention centers. Because the Kurds had been so valuable to America, and because they were the only group controlling ISIS prisoners, they became powerful and independent.

The Kurds did something innovative with this independence. They controlled oil and gas fields in their territory. They pumped oil and ran local refineries. They sold diesel and electricity. The money from oil sales paid government workers' salaries, gave free electricity to citizens, and funded the military and police. This economic independence made them less vulnerable to pressure from neighboring countries.

By 2025, the Kurds had become comfortable. They had a ten-year track record of self-governance. They had American military protection. They had oil money. They thought they were secure.

Then the Syrian government changed.

The New Government and Turkish Pressure

The Danger Signal

In December 2024, the Assad regime fell. A new Syrian government, led by Ahmed al-Sharaa, took power. This new government wanted to do something the old government had been too weak to do: consolidate control over all Syrian territory.

The new Syrian government looked at the map and saw a problem. The Kurds controlled about 30 percent of Syria's northeast. They had their own army, government, police, and courts. They weren't listening to Damascus. More importantly, they were sitting atop Syria's oil fields.

From the Syrian government's perspective, this wasn't acceptable. They wanted to rebuild Syria's economy, which was destroyed by fourteen years of war. They needed oil revenue. They needed to prove to their people that they could restore order and bring the national territory back under central control. They looked at the Kurdish-controlled areas and saw a threat to their national vision.

Turkey added crucial pressure. Turkish officials announced a deadline: December 31, 2025. The Kurds had to integrate into the Syrian government by that date. Why was Turkey so insistent? Because Turkey has its own problem with Kurds. The Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) has been fighting the Turkish government for decades. Turkey believed that the Kurdish group in Syria—called the YPG—was connected to the PKK. As long as armed Kurds existed in Syria, Turkey worried they could support Kurdish militants in Turkey itself.

Turkish officials made obvious statements. In January 2026, the Turkish Foreign Minister said, "The SDF has no chance of getting anything done through dialogue without the threat of force." This was not a diplomatic hint. This was a signal that Turkey would support military action to force Kurdish integration.

The Failed Negotiations

When Talking Breaks Down

In March 2025, a peace agreement was reached. The Syrian government and the Kurds agreed on a framework for integrating SDF forces into the Syrian military. Both sides promised they would work together. The deadline was December 31, 2025.

But nothing happened. The negotiations stalled. Month after month, talks continued but didn't progress. The Kurds wanted to keep their soldiers organized in separate units. They wanted recognition of their rights in the Syrian constitution. They wanted guarantees that oil money would be shared fairly. The Syrian government said these demands were unacceptable. They wanted complete integration, with Kurdish soldiers becoming regular Syrian army soldiers answering to Damascus, not Kurdish commanders.

By December 2025, the deadline passed. The Kurds had not agreed to the government's terms. The Kurdish leadership had bet on something: they believed that if they held firm, they could force better terms. They had the oil. They had the U.S. military. They had the ISIS prisoners in their jails. They thought they had leverage.

This was a catastrophic miscalculation.

The Military Collapse

Two Weeks That Changed Everything

On January 6, 2026, fighting erupted in the city of Aleppo, which was partly controlled by the Kurds and partly by the Syrian government. This wasn't random fighting. This was the start of a coordinated military plan. The Syrian government, coordinated with Turkish military advisors, launched an offensive against SDF-held territory.

The fighting spread quickly. Syrian government forces advanced into the Raqqa province and the Deir ez-Zor province. These are the oil-rich areas. These are where the biggest military bases are.

What happened next surprised everyone. The SDF's army fell apart in two weeks.

Why? Because about 40 percent of the SDF's soldiers were Arab, not Kurdish. When the Syrian government—an Arab government—fought against them, many Arab soldiers didn't want to fight their own people. They deserted. They switched sides. They joined the government forces. Whole units just disappeared. Imagine if 40 percent of your employees suddenly quit in the same week—your business collapses.

Within fourteen days, the Syrian government controlled Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor. They controlled the oil fields. The Kurds had to retreat east of the Euphrates River. SDF leader Mazloum Abdi realized they were losing. The military situation had become hopeless.

American Betrayal: The Final Blow

Here's what the SDF expected to happen. When they started losing militarily, they expected the United States to help. Maybe not with ground troops, but with air strikes. Or diplomatic pressure. Or public statements of support. After all, the Kurds had fought ISIS for the U.S. The Kurds had died for the U.S. They had a partnership.

It didn't happen.

Instead, the U.S. special envoy to Syria, Tom Barrack, met with Syrian President al-Sharaa and told him that America supported the Syrian government's integration plan. More than that, Barrack said on January 21: "The SDF's role in counter-terrorism has largely expired. We have no interest in extending a separate SDF role."

Translation: You are no longer helpful to us. We are switching sides.

For the SDF, this was betrayal at the worst possible moment. They were losing a war and discovered their main ally had abandoned them.

Why did the U.S. do this? Several reasons. First, the Trump administration has decided that a strong, centralized Syrian government under al-Sharaa is better for American interests than a divided Syria with Kurdish autonomy. Second, the U.S. wants to focus on containing Iranian influence in Syria. The American calculation is that a unified Syrian government is easier to pressure and cooperate with than a decentralized system. Third, the U.S. doesn't want the long-term burden of protecting the Kurds. That's expensive in military terms and diplomatic terms.

From the American perspective, it was a strategic calculation. From the Kurdish perspective, it was abandonment.

The Deal: What the Kurds Lost

By January 18, 2026, the SDF had no choice but to negotiate. On January 20, they agreed to a ceasefire. But the truce came with conditions—conditions the government imposed, not negotiated.

Here is what the Kurds lost

Oil Fields and Economic Power

The Syrian government took complete control of all oil fields, including Al-Omar, Al-Tanak, and Conoco. The Kurds no longer have oil revenue. They can no longer pay government workers' salaries. They can no longer provide free electricity. This is like a family losing its job while trying to pay the mortgage.

Territorial Control

The Kurds lost control of Raqqa province and Deir ez-Zor province. They lost over half the territory they controlled before. They are now limited to Al-Hasakah province, a Kurdish-majority area in the far northeast near the Turkish border.

Military Independence

Instead of organizing their soldiers into separate Kurdish units within the Syrian army—which they wanted—their soldiers will be integrated individually as regular army soldiers. This means Kurdish commanders will not lead Kurdish soldiers. Kurdish military identity is dissolved into the Syrian military.

Detention Facilities

The Kurds ran large prisons and camps holding approximately 9,000 ISIS fighters and their families. The Syrian government took control of these facilities. The prisoners—terrorists who have killed thousands of people—are now the responsibility of Damascus.

What They Were Promised: The Uncertainty Problem

The Syrian government gave the Kurds some promises in return:

A presidential decree recognizing Kurdish as a national language alongside Arabic. The decree restores citizenship to Kurds who had been denied it. It says Kurdish can be taught in schools.

A promise that Syrian government forces will not enter Kurdish villages. This means Al-Hasakah province will remain under SDF administration.

A promise that some Kurds can hold positions in the Syrian government, including a position as assistant defense minister.

But here is the problem: these are promises only, not constitutional rights. They are not written into Syria's permanent constitution. A promise can be broken. A presidential decree can be reversed. History shows that minority protections based on promises rather than constitutional law often don't survive changes in government or pressure from majority groups.

The Kurds learned this the hard way. They gave up permanent control of territory and resources in exchange for temporary promises.

ISIS and Detention Security: A Growing Danger

When the Syrian government took over the detention facilities, the chaos started immediately. Prisoners began escaping. At the al-Shaddadi prison, between 81 and 1,500 prisoners broke out. Different sources report different numbers because no one is certain exactly what happened in the confusion.

This is dangerous because these are not ordinary criminals. These are ISIS fighters and supporters. ISIS has a specific plan: break their people out of prison, reconstitute their military forces, and take back territory. They have done this before.

There are about 9,000 ISIS fighters in Syrian detention facilities. Additionally, about 24,000 people are in camps—primarily women and children of ISIS members. Many of these prisoners are foreign nationals from countries like Tunisia, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan. These countries don't want them back because they consider them security threats.

The U.S. military decided the situation was too dangerous. Starting in late January 2026, the U.S. military began transferring prisoners to Iraq. The plan is to move up to 7,000 ISIS fighters from Syria to Iraqi prisons.

This creates a new problem: Iraq already has thousands of ISIS prisoners, and Iraq's government is not necessarily more capable of managing them than the Kurds were. Plus, this shifts the security burden to Iraq, which is also unstable.

ISIS Threat: The Numbers

ISIS is still dangerous, even though it lost its territory in 2019. During 2024, ISIS conducted almost 700 attacks in Syria and Iraq. That was triple the number in 2023. The organization is getting stronger, not weaker.

Why? Partly because the military instability in Syria is giving them opportunities. Partly because there are thousands of ISIS fighters in detention who could be freed. Partly because the organization has proven adaptable and resilient.

ISIS's primary targets remain Syria and Iraq, but the organization has a presence in Libya and other countries. The bigger the chaos in Syria and Iraq, the more opportunity ISIS has to expand.

What Happened in Iraq: The Broader American Withdrawal

While the Kurds were losing Syria, the United States was also completing its military withdrawal from Iraq. By January 2026, the U.S. finished pulling out of all major bases in Iraq except for a small presence in the Kurdish region.

This matters because Iraq is also fragile. ISIS also threatens Iraq. Iraq also has militias connected to Iran that destabilize the country.

The U.S. is now moving thousands of ISIS prisoners from Syria into Iraq. This is like taking a significant security problem in Syria and placing it into Iraq, which is already struggling with security problems of its own.

Additionally, the U.S. is imposing financial sanctions on Iraqi institutions and individuals connected to Iran. The U.S. is scrutinizing Iraqi bank transfers and money movements. The purpose is to prevent Iraq from becoming too close to Iran, but the effect is to create financial pressure on Iraq's fragile economy.

Why did the U.S. abandon Iraq? The Bush administration invaded Iraq in 2003 based on false claims about weapons of mass destruction. The invasion destabilized the country, cost nearly 5,000 American lives, and created the conditions for ISIS to emerge. After almost two decades, the U.S. decided to leave. But it left behind a country that is divided between Iran's sphere of influence and the U.S. sphere of influence, a country with ongoing security threats, a country with corruption problems, and a country that now has to manage thousands of additional ISIS prisoners transferred from Syria.

The U.S. has shifted the burden of managing Middle East security problems to countries less capable of managing them.

Could Kurdistan Have Been Established: The Question the Kurds Ask

This leads to the question the Kurdish leadership now asks itself: could we have done things differently? Could we have achieved independence instead of accepting integration?

Technically, the Kurds have some historical precedent for independence. Iraqi Kurdistan has its own government and operates semi-autonomously within Iraq. Turkish Kurdistan has its own political movements. Syrian Kurdistan is the most advanced Kurdish self-governance experiment in the world.

But the reality is stark: no major country supports Kurdish independence in Syria. The U.S. withdrew support when it calculated that a unified Syria was more valuable than Kurdish autonomy. Turkey opposes Kurdish independence because it fears links to the PKK. Iran opposes it because it opposes any non-state authority in Syria. The Arab countries are divided but lean toward opposing Kurdish secession.

Could the Kurds have fought on? Theoretically, yes, but they would have faced:

A much larger Syrian military backed by Turkey

Withdrawal of American military support

Depletion of their economic resources (lost oil money)

Defection of their Arab soldiers

International isolation without any supporters

Realistically, independence became impossible the moment the U.S. switched sides.

The Broader Meaning: Why This Matters Beyond Syria

This situation teaches several important lessons about the Middle East and American foreign policy.

First, U.S. partnerships are conditional. The Kurds learned what many allies have learned: American support depends on American interests. When American interests shift, partnerships can be abandoned. This makes regional actors hesitant to rely on American promises.

Second, geography is destiny in the Middle East. The Kurds are split across four countries: Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. They will always be a minority in each country. Unless all four countries simultaneously support Kurdish independence—which is impossible—the Kurds cannot achieve a unified state. They can only hope for autonomy within existing states, which is always vulnerable to changes in government and regional power balances.

Third, control of oil and economic resources determines political power. The SDF lost when they lost the oil fields. As long as they controlled the oil, they had leverage. Once they lost the oil, they had nothing left to negotiate with.

Fourth, military force ultimately determines outcomes when politics fail. The SDF tried to negotiate for over a year. The negotiations failed. Then the stronger military side—the Syrian government—used force to achieve what it couldn't negotiate. The SDF was forced to accept terms they had rejected during negotiations because the alternative was military defeat.

Fifth, terrorism and detention security remain fragile. Thousands of ISIS prisoners remain in custody, but that custody is only secure as long as the organization managing them remains stable and focused on that mission. Political instability creates opportunities for terrorist organizations to break their people out of prison.

The Future

Three Scenarios

What happens next for the SDF? Three scenarios are possible.

Scenario 1

Successful Integration. The SDF integrates peacefully into the Syrian military. Kurdish soldiers and officers gain positions of responsibility. The Syrian government respects its promise to allow the SDF to govern Al-Hasakah. The Kurdish language and rights are recognized. This would represent the best outcome the Kurds can achieve at this time—probability: 40 percent.

Scenario 2

Gradual Erosion. The Syrian government technically honors the integration agreement, but slowly erodes SDF autonomy. Kurdish officials are sidelined. Government officials gradually replace SDF administrators. Kurdish military influence diminishes. By 2030, the SDF exists only as a label with no real power. This is the most likely scenario—probability: 50 percent.

Scenario 3

Complete Dissolution. The Syrian government breaks the agreement and takes complete control of Al-Hasakah. The SDF is dissolved. Kurdish officials are arrested or flee. Armed resistance erupts. Turkey joins a Syrian government offensive. The Kurds are defeated militarily—probability: 10 percent.

The most likely outcome is gradual erosion. The SDF will no longer exist as an independent force, but the name will persist as a label for Kurdish units within the Syrian military.

Conclusion

The Cost of Miscalculation

The Syrian Democratic Forces had the best opportunity for Kurdish autonomy in the modern Middle East. They had military strength. They had territory. They had economic resources from oil. They had American military support. They had defeated a terrorist organization.

But they miscalculated at a critical moment. They assumed that American support was permanent. They thought that economic leverage would give them political power. They believed that the new Syrian government couldn't win a military confrontation. They assumed that neighbors would not coordinate against them.

All of these assumptions were wrong.

The cost of these miscalculations is clear: loss of territorial control, economic independence, military autonomy, and the ability to make their own decisions.

The broader lesson is clear: in the Middle East, political arrangements depend ultimately on the willingness of regional and international powers to support them. When those powers change their calculations, arrangements that seemed secure can collapse in a matter of weeks. The SDF is learning this lesson at enormous cost. Other regional actors are watching and learning the same lesson.