Israel’s Somaliland Recognition: Strategic Realignment and the Crisis of International Consistency -Part I

Executive Summary

Israel’s December 26, 2025 recognition of Somaliland as an independent state represents the first formal diplomatic acknowledgment by any United Nations member country, breaking a 34-year diplomatic impasse.

This decision constitutes a fundamental recalibration of Israel’s geostrategic posture, prioritizing maritime security in the Red Sea and expanding the Abraham Accords framework into sub-Saharan Africa.

The recognition has sparked coordinated diplomatic backlash from Somalia, Egypt, Turkey, and Djibouti, while simultaneously raising profound questions about the consistency of Israel’s positions regarding self-determination, territorial sovereignty, and Palestinian statehood. While Palestinian resettlement to Somaliland figured prominently in earlier discussions, the absence of such language in the formal recognition suggests this element was either rejected or deprioritized.

The move catalyzes a regional power realignment centered on port competition, Red Sea security, and the contest between Chinese and Western strategic influence in the Horn of Africa.

The Trump administration’s anticipated response will determine whether Israel’s recognition serves as a watershed moment for broader international acknowledgment or remains an isolated diplomatic anomaly.

Introduction

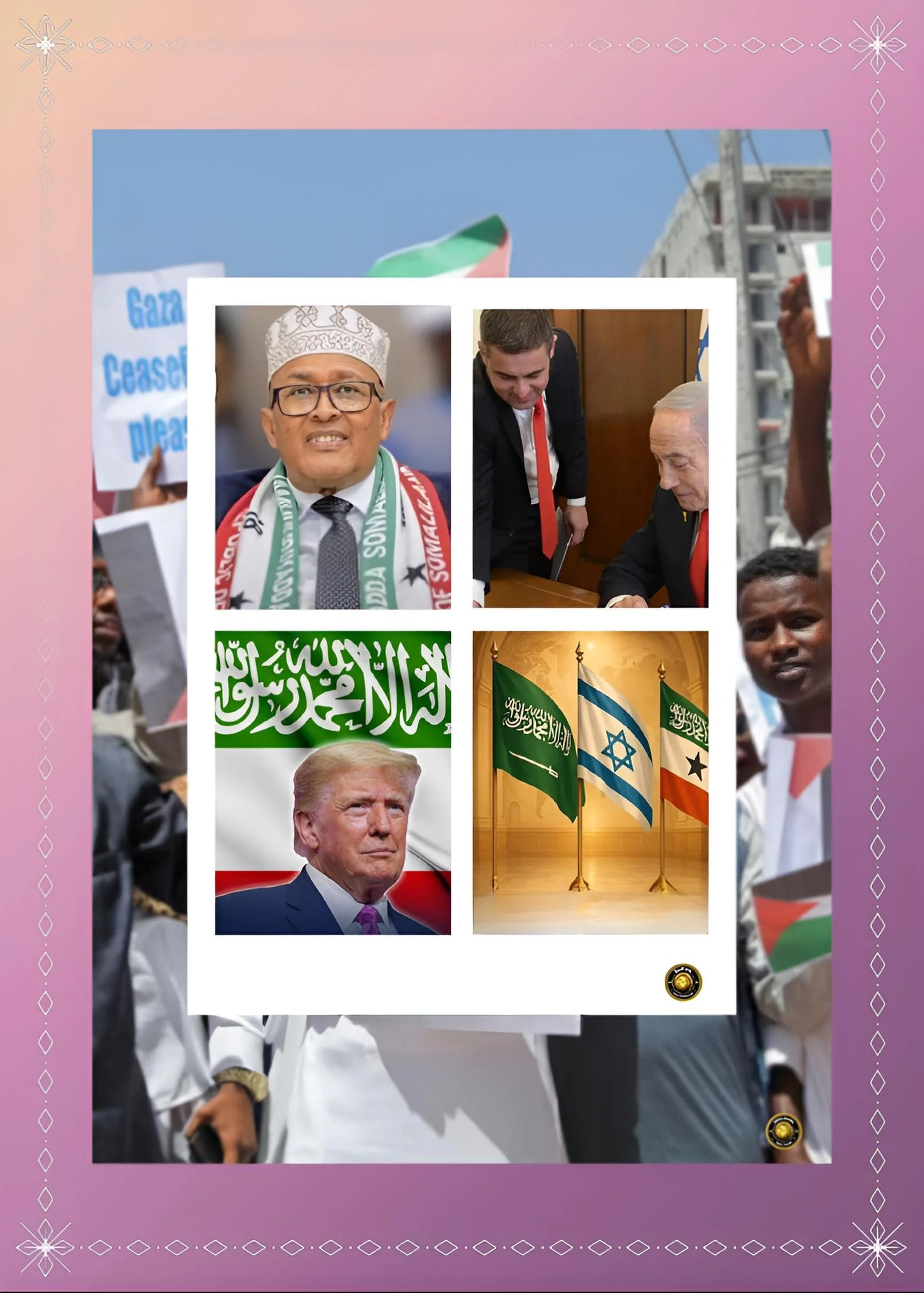

The recognition of Somaliland by the State of Israel on December 26, 2025, initiated by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar alongside Somaliland President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi, marks a consequential inflection point in Horn of Africa geopolitics and Middle Eastern diplomatic strategy.

The formal declaration, characterized by Israeli officials as advancing “the spirit of the Abraham Accords” initiated by the Trump administration, emerged after approximately one year of confidential negotiations led by Israeli intelligence, particularly Mossad, and the Israeli Foreign Ministry.

This recognition introduces both immediate strategic advantages and profound long-term complications for the regional order and international legal precedent.

The significance of this moment extends beyond bilateral diplomatic relations. The recognition implicitly challenges established African Union doctrine regarding border inviolability—a foundational principle established in 1964 to prevent colonial boundary disputes from destabilizing the entire continent.

Simultaneously, it resurrects the contested question of how self-determination principles ought to apply selectively across different contexts, forcing the international community to confront apparent hypocrisy in how Israel treats Palestinian statehood claims versus Somaliland’s independence aspirations.

Furthermore, the strategic calculations driving Israeli recognition reveal the deepening competition for maritime access, intelligence positioning, and geopolitical alignment in the Horn of Africa as major powers contest for influence in a region of accelerating strategic importance.

This analysis examines the recognition event within its complete historical, geopolitical, and legal contexts, assessing the underlying motivations, the speculative dimensions regarding Palestinian resettlement, the regional consequences, and the implications for international law and diplomatic consistency.

Historical Context and the Somaliland Question

Somaliland’s path toward independence represents a unique postcolonial narrative shaped by distinct colonial legacies, regional ethnic identities, and the catastrophic failure of Somali state institutions.

To understand the significance of Israel’s recognition, one must comprehend how Somaliland emerged as a self-governing entity and why international recognition has remained perpetually beyond reach despite three decades of functional statehood.

The territory known today as Somaliland constitutes the former British protectorate of Somaliland, colonized by the British Empire in the nineteenth century and maintained as a separate administrative entity until 1960.

In a remarkable historical occurrence, Somaliland achieved five days of internationally recognized independence in June 1960, during which Israel and thirty-four other countries extended formal diplomatic recognition. This brief independent interregnum ended on June 26, 1960, when Somaliland voted to join Italian Somalia to create the unified Somali Republic, a decision made through popular referendum that has become progressively contested within Somaliland as a misjudgment in hindsight.

The unified Somali state rapidly descended into centralization and marginalization of the northern regions from which Somaliland emerged. The military junta of President Siad Barre, seizing power in 1969, conducted systematic suppression and warfare against Somaliland’s predominantly Isaaq clan population. Between 1982 and 1989, the Barre regime killed tens of thousands of Somalilanders and destroyed much of the region’s infrastructure in what international observers characterized as genocidal violence. The Somali National Movement, emerging in Somaliland as a rebellion against the junta, ultimately participated in the broader coalition that ousted Barre in January 1991.

Critically, while other Somali militia factions remained locked in competition for control of Mogadishu and the southern state apparatus, Somaliland’s leaders opted for separation rather than competing for dominance in a collapsing national structure.

In May 1991, Somaliland unilaterally declared independence, establishing a government structure centered in the capital of Hargeisa. This declaration occurred within the broader context of complete Somali state collapse—the unified Somali republic had essentially ceased to function as an organized state apparatus by 1991, making Somaliland’s separation not a fracturing of a functioning polity but rather a reconstitution of its distinct colonial-era identity.

For three decades following independence, Somaliland functioned as a de facto sovereign state despite complete absence of international recognition. The territory established its own currency (the Somaliland Shilling), issued its own passports, maintained security forces, and conducted its own foreign policy. More significantly, Somaliland constructed democratic institutions that contrasted sharply with the anarchic conditions prevailing in Somalia proper.

Beginning in 2003, Somaliland transitioned from a power-sharing arrangement among major clans to a multiparty democratic system that, despite periodic crises and institutional stresses, has delivered peaceful electoral transfers of power.

The 2024 presidential election marked a watershed democratic achievement: Somaliland conducted a transparent electoral contest in which the opposition Waddani party defeated the incumbent, with the incumbent accepting the result peacefully. This outcome made Somaliland one of only five African states to experience such a contested and peaceful power transfer in 2024.

Yet despite this institutional accomplishment, Somaliland has remained perpetually locked outside the international state system. The fundamental obstacle has been the African Union’s unwillingness to recognize border changes except in the cases of Eritrea (1993) and South Sudan (2011)—both instances involving negotiated agreements with parent states. Somaliland’s unilateral declaration of independence, without comparable agreement from Mogadishu, placed it in diplomatic limbo. The AU reasoned that recognizing Somaliland would establish a precedent encouraging other secessionist movements (Biafra in Nigeria, Western Sahara, Anglophone Cameroon, and countless others) to seek external validation and international legitimacy, potentially destabilizing the entire continental order.

This diplomatic impasse created profound economic consequences. Somaliland’s exclusion from the international state system rendered it ineligible for loans from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, restricted its access to international trade mechanisms, and prevented it from negotiating as a sovereign entity in most international forums.

The territory’s GDP per capita—approximately 1,500 dollars annually—reflects not lack of economic potential but rather the consequences of diplomatic isolation. Most economic activity depends on remittances from Somalilanders working in the diaspora and traditional livestock exports to neighboring Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Gulf states. Unemployment remains persistently high, particularly among youth, creating what officials term a potential “brain drain” as educated populations migrate seeking opportunities elsewhere.

Somaliland’s stability, democracy, and institutional development thus occurred entirely outside the international system, recognized by select countries through liaison offices and informal relationships but formalized by no UN member state.

This historical context illuminates why Israeli recognition, whatever its strategic drivers, carries such profound significance for Somaliland’s leadership and population—it breaks the longest uninterrupted period of diplomatic non-recognition any functioning state apparatus has endured in the postcolonial era.

Current Status and Recent Developments

As of late 2025, Somaliland operates as a functioning state apparatus controlling territory comprising approximately the northern third of the geographic area internationally recognized as Somalia.

The territory encompasses roughly six million people, predominantly from the Isaaq clan, speaking Somali with distinct dialectical characteristics and maintaining distinct cultural practices that have solidified Somaliland identity separate from broader Somali nationalism.

The election conducted in November 2024 resulted in the victory of Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi, commonly known as Irro, representing the opposition Waddani party. Irro has prioritized international recognition as his defining national objective, understanding that Somaliland’s integration into the international state system constitutes the sine qua non for economic development and security guarantees. His administration has pursued recognition aggressively through diplomatic channels, international organizations, and bilateral negotiations with potential recognizing states.

Somaliland’s strategic importance has been amplified by its geopolitical location along the entrance to the Red Sea and in proximity to the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, through which approximately one-third of global maritime shipping transits.

The port of Berbera, located on Somaliland’s northern coast, has emerged as the focal point of regional strategic competition. In 2016, Somaliland negotiated a landmark concession agreement with DP World of Dubai (part of the United Arab Emirates) to develop and manage Berbera, an arrangement expected to generate millions of dollars of annual income for Somaliland and transform it into a regional port hub.

The strategic dimensions of Berbera intensified dramatically with the January 2024 memorandum of understanding between Somaliland and Ethiopia.

Under this agreement, landlocked Ethiopia gained rights to approximately twelve miles of Somaliland coastline and fifty-year leasing rights for commercial and military access to Berbera, ostensibly in exchange for future recognition and partial ownership of Ethiopia Airlines, the national carrier. This arrangement represented a significant geopolitical statement—Ethiopia, whose development has been constrained by landlocked status and dependence on Djibouti as its primary ocean gateway, achieved an alternative Red Sea outlet.

The MOU triggered immediate backlash from Somalia, which characterized the agreement as an illegal act of aggression and recalled its ambassador to Ethiopia. Somalia also threatened to withdraw Ethiopian peacekeeping forces deployed under UN auspices to combat al-Shabaab, raising the prospect of regional destabilization. Turkey-mediated diplomatic talks eventually thawed Ethiopian-Somali tensions by 2024, though Somalia secured an agreement stipulating Ethiopia would pursue port access “under Somalia’s sovereignty,” complicating the status of the Somaliland MOU.

These developments establish the backdrop for understanding why Somaliland’s international recognition has become both more urgent and more complex. The territory has positioned itself as a critical node in Red Sea geopolitics at precisely the moment when global powers are competing intensely for control of maritime chokepoints, port facilities, and regional alignment.

Somaliland has proven willing to engage foreign powers directly in investment agreements, military partnerships, and strategic negotiations, despite formal non-recognition. Yet this de facto international engagement without de jure status creates legal ambiguities, vulnerability to challenges from Somalia, and constraints on the scale of investments and partnerships Somaliland can negotiate.

Israel’s Strategic Calculus and Motivations

The Israeli decision to recognize Somaliland emerged from a complex intersection of immediate security concerns, long-term strategic positioning, and domestic political considerations.

Prime Minister Netanyahu’s announcement, released on December 26, 2025, explicitly framed the recognition within “the spirit of the Abraham Accords” while simultaneously emphasizing shared security interests, regional stability, and economic cooperation. Yet the underlying motivations reveal deeper strategic imperatives driving Israeli policy.

The most immediate driver concerns Red Sea security and maritime access. Since the October 2023 initiation of Israel’s military operations in Gaza, Iranian-backed Houthi forces in Yemen have systematically attacked commercial shipping transiting the Red Sea, claiming solidarity with Palestinians. These attacks have inflicted hundreds of millions of dollars in losses on global commerce, prompted major shipping companies to reroute around Africa via the Cape of Good Hope, and created genuine physical threats to Israeli maritime traffic. Eilat, Israel’s primary outlet to Asia and Africa via the Red Sea, has been rendered partially unusable by Houthi threats. The acquisition of strategic positioning in Somaliland and relationship with Berbera port provides Israel with advanced warning systems, intelligence collection capabilities against Houthi positions across the narrow strait separating Somaliland from Yemen, and potential military cooperation advantages. Israeli officials have stated publicly that Mossad chiefs maintained long-standing personal relationships with Somaliland officials and leveraged these connections to advance recognition negotiations—suggesting the relationship carries intelligence cooperation dimensions.

Beyond immediate maritime security, Israel’s recognition reflects a broader strategic reorientation toward the Horn of Africa as a critical arena for countering Iranian influence and Chinese expansion.

The Abraham Accords, initially conceived as Arab-Israeli normalization focused on shared Iran concerns, have evolved into something considerably more expansive—a US-led geopolitical coalition transcending Arab identity and the traditional Middle East region.

The framework originally encompassed the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain (2020), subsequently incorporated Sudan and Morocco (2020), and has been proposed for expansion to Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan.

The inclusion of Somaliland represents the first non-Arab, sub-Saharan African entry into the framework, signaling an intentional geographic expansion toward regions of strategic interest.

This expansion reflects calculations about Chinese influence in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean regions. China’s strategic expansion via the Belt and Road Initiative has extended Chinese naval presence through Djibouti, where China maintains its first permanent overseas military facility. China has invested substantially in Port of Aden in Yemen, maintains relationships with Iran and Iranian proxies, and has positioned itself as a major stakeholder in Indian Ocean maritime commerce.

Israel’s recognition of Somaliland and positioning at Berbera represents a Western counter to Chinese strategic consolidation, creating an alternative alignment centered on US-led relationships with pro-Western regional authorities. The pattern mirrors broader Trump administration interest in building coalitions transcending traditional regional boundaries and focused on shared strategic interests rather than ideological alignment.

A third strategic dimension concerns Israel’s broader African positioning. Israeli officials have acknowledged that the state has experienced increasing isolation internationally during the Gaza war, with multiple countries recalling ambassadors, joining International Court of Justice cases against Israel, and engaging in boycott-divestment-sanction campaigns.

The expansion of Israeli diplomatic presence and influence in Africa represents a deliberate strategy to diversify relationships and maintain regional influence despite constrained relationships in Europe and parts of the Americas. Israel reopened its embassy in Zambia in August 2025 after more than fifty years—a symbolic return to African engagement.

The Somaliland recognition fits within this broader strategic reorientation toward Africa as a continent where Israel can expand influence and construct relationships outside the fraught Middle Eastern context.

Netanyahu’s personal framing of the recognition as contributing to regional stability reflects a final consideration: the move positions Israel as a rational actor pursuing legitimate security interests rather than expansionist aggression. By characterizing Somaliland recognition as acknowledging “existing reality”—that Somaliland has functioned as an independent state with democratic institutions and peaceful transfers of power for three decades—Israeli officials invoke a de facto statehood argument. Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar stated explicitly that “this is not a provocation, but an opportunity to enhance stability.” This framing attempts to distance the recognition from accusations of destabilization or hypocrisy by emphasizing that Israel recognizes an already-functioning polity rather than catalyzing new state fragmentation.

Yet this framing confronts significant logical problems when examined against Israeli positions regarding Palestinian statehood, as subsequent analysis will demonstrate.

The Palestinian Resettlement Dimension: Speculation, Fact, and Absence

Perhaps the most contentious and emotionally charged dimension of the Somaliland recognition concerns speculation about Palestinian resettlement to Somaliland territory. The user’s query explicitly identifies this concern, and the international literature contains substantial reporting on this topic. Understanding what can be factually established versus what remains speculative requires careful chronological examination.

The timeline of documented events begins with former US President Donald Trump’s February 2025 public proposal to relocate Gaza residents elsewhere for an unspecified period. Trump argued that Gaza had become uninhabitable following the Israel-Hamas war and suggested that displaced Palestinians might be resettled in third countries with subsequent rehabilitation of Gaza by US administration. In characteristic Trump fashion, he stated “We’ll own it, we’re going to take over that piece, develop it and create thousands and thousands of jobs.” This proposal triggered immediate backlash across the Arab world and Europe, though Trump did not withdraw it despite stating that Palestinians would not be forced to leave.

Following this public statement, the Associated Press reported in March 2025 that US and Israeli officials had formally approached Sudan, Somalia, and Somaliland exploring possibilities for Palestinian resettlement.

According to US official sources cited by the AP, Israel took the lead in these discussions. However, critically, officials in Sudan denied any interest, while officials in Somalia and Somaliland stated they were unaware of any such discussions. This asymmetry between reported US-Israeli outreach and the denials from recipient countries established ambiguity about the actual status of resettlement negotiations.

As the year progressed, Trump himself appeared to retreat from the explicit language of forced Palestinian relocation. In March 2025, Trump stated “Nobody is expelling any Palestinians,” suggesting either recalibration of the proposal or recognition that the political costs had become prohibitive. This statement effectively deprioritized the resettlement concept as a formal US policy objective.

In December 2025, coinciding with Israel’s formal recognition announcement, Raxanreeb Media, a Somaliland-focused news outlet, reported that Somaliland had approved plans to accept approximately 200 Palestinians described as “supporting Israel.” The report cited unspecified sources and explicitly noted the absence of official Somaliland government confirmation. This unverified report appears designed to maximize controversy while maintaining plausible deniability regarding accuracy.

Crucially, the formal December 26, 2025 recognition document signed by Netanyahu and Somaliland President Irro contains zero mention of Palestinian resettlement.

The official joint declaration addresses economic cooperation, agriculture, health, technology, and mutual recognition, but completely omits any reference to Palestinian populations, displacement, or resettlement. This conspicuous absence from the formal agreement suggests several possibilities: the resettlement concept was rejected by Somaliland leadership as politically untenable, Trump administration prioritization of the concept shifted after March 2025, or the concept was explored but deemed insufficiently valuable to include in a formal agreement.

The Somaliland domestic perspective on forced Palestinian displacement reveals profound opposition. Human rights advocate Guleid Ahmed Jama emphasized that Somaliland’s constitution explicitly respects international law and that forced Palestinian displacement would violate that commitment and render Somaliland complicit in genocide. Jama argued that international recognition achieved through enabling Palestinian ethnic cleansing would generate diplomatic isolation comparable to Israel’s current position.

Somaliland residents interviewed by Middle East Eye expressed strong support for Palestinian self-determination but unambiguous opposition to forced displacement framed as a condition for international recognition. Mohamed, a Hargeisa resident, stated that forced Palestinian displacement would mean “the loss of their homeland,” and predicted that announced acceptance of Palestinians would trigger armed domestic resistance within Somaliland.

Researcher Omar Mahmood of the International Crisis Group assessed that Palestinian resettlement “alone is unlikely to be sufficient” as a recognition incentive and would be “politically combustible within Somaliland.” This expert assessment suggests that even if Trump administration officials proposed resettlement as part of broader negotiations, Somaliland leadership would likely reject it as an explicit condition due to domestic political costs.

The economic dimension further undercuts the resettlement narrative. Somaliland’s territory encompasses approximately six million people, economic infrastructure designed for this population base, and land scarcity created by pastoral economies and clan territorial claims.

Introducing hundreds of thousands or millions of Palestinian refugees would generate severe resource competition, clan-based tensions, and potential violent conflicts. Dr. Abdifatah Ismael Tahir of the University of Manchester noted that “limited economic opportunities, scarcity of land, and the potential for clan-based tensions” would present substantial obstacles to large-scale Palestinian settlement.

The UAE’s role as a primary advocate for Somaliland recognition, while simultaneously seeking to control Berbera’s trade routes and counter Djibouti’s influence, suggests UAE interests center on port control and regional positioning rather than Palestinian resettlement facilitation.

The assessment therefore establishes that while Palestinian resettlement figured in preliminary discussions during spring 2025, the concept appears to have been abandoned, rejected, or deprioritized well before the December recognition.

The formal recognition document’s complete omission of resettlement language, combined with expert assessment of domestic political impossibility within Somaliland, suggests that any resettlement component was contingent rather than foundational to the recognition decision.

Israeli recognition proceeded on pure strategic grounds regarding Berbera, Red Sea access, and regional positioning—the Palestinian dimension, while historically significant as an explored option, did not constitute a binding condition or primary strategic objective.

This assessment carries important implications for understanding Israeli motives and international accountability. If Palestinian resettlement remains contingently under discussion despite formal recognition, it would constitute a hidden agenda undermining international law.

Conversely, if resettlement has been genuinely abandoned, it suggests Israeli strategic thinking has moved beyond displacement scenarios toward direct security cooperation models.

The absence of resettlement language in the formal recognition implies the latter interpretation is more credible, though continued vigilance regarding implementation remains warranted.

The Hypocrisy Paradox: Gaza, Palestine, and Somaliland

The recognition creates a documented, observable contradiction in Israel’s international legal positions that demands explicit analysis. This contradiction has not gone unnoticed by observers, most pointedly by Israeli officials themselves.

A senior Israeli official quoted by Channel 12 television crystallized the logical inconsistency: “All the countries of the world except for Israel see Somaliland as an integral part of Somalia. The decision to recognize Somaliland as an independent country completely undermines Israel’s argument against recognizing an independent Palestinian state.” This statement, emerging from within Israel’s own policy establishment, identifies the structural hypocrisy with precision and candor.

The contradiction operates as follows at the doctrinal level. Israel has consistently opposed Palestinian statehood on grounds including sovereignty concerns, refugee rights complications, security vulnerabilities from a Palestinian state, and the principle that territorial integrity of recognized states should not be violated by separatist fragmentation. These arguments, deployed across decades in international forums, in bilateral negotiations, and in US policy discussions, establish a coherent doctrinal framework: Israel opposes the creation of new states through separation from existing internationally recognized polities.

Israel’s Somaliland recognition, by contrast, explicitly endorses the creation of a new state through separation from an existing internationally recognized polity (Somalia). The recognition declares that Somaliland, despite Somalia’s opposition and without Somalia’s consent, qualifies for independent statehood based on demonstrated stability, democratic governance, peaceful power transfers, and distinct identity. Somaliland has indeed demonstrated these attributes across three decades. Yet the logical extension of Israel’s position would be that these same attributes equally support Palestinian statehood claims—Palestinians have demonstrated governance capacity in areas where they exercise control, have conducted elections that international observers have monitored, and possess distinct identity and cultural traditions.

Somalia’s response weaponized this contradiction directly. Somalia’s December 25 statement jointly issued with Egypt, Turkey, and Djibouti explicitly connected the issues. By simultaneously defending its territorial integrity against Somaliland while invoking Palestinian solidarity, Somalia established a rhetorical parallel: just as Somalia rejects Somaliland’s separation, Palestinians deserve equivalent international support against territorial partition. This rhetorical maneuver may lack force as legal argument, but it possesses considerable diplomatic power—it positions Israel as applying self-determination principles selectively based on political convenience rather than consistent legal reasoning.

The Israeli counterargument to charges of hypocrisy relies on distinguishing factors. Israeli officials might contend that Somaliland has achieved governance capacity, institutional stability, and democratic functioning superior to Palestinian governance structures. Palestinian territories, fragmented between West Bank and Gaza, with contested governance between Palestinian Authority and Hamas, and constrained by Israeli military occupation, arguably present governance challenges distinct from Somaliland’s context. Furthermore, Israeli officials have argued that Israel’s recognition does not establish international precedent requiring Palestine recognition—Somaliland recognition is presented as acknowledging existing reality rather than creating new legal doctrine.

However, this counterargument faces substantial vulnerabilities. If Israel’s position is that self-determination applies only to territories demonstrating superior governance capacity, institutional strength, and democratic development, then Palestinians would merely need to demonstrate comparable institutional improvements to claim equivalent recognition. Such a framework provides Palestinians with a roadmap for building the governance structures that would justify recognition—arguably a more coherent international legal standard than one applying self-determination selectively based on political convenience.

More fundamentally, the hypocrisy operates at a level deeper than doctrinal consistency. It concerns the selective application of international law principles based on strategic interest. Israel recognizes Somaliland because strategic interests in Red Sea access, counter-Iran positioning, and Abraham Accords expansion align with Somaliland’s independence. Israel opposes Palestinian statehood because Palestinian sovereignty would constrain Israeli strategic options in the West Bank and create a state perceived as potentially hostile. The underlying calculus privileges strategic advantage over legal consistency.

This selective application will constrain Israel’s diplomatic standing regardless of strategic benefits gained through Somaliland recognition. The precedent is now established in documented form—an Israeli official has publicly acknowledged that Somaliland recognition contradicts Palestinian statehood opposition. This acknowledgment circulates globally in Palestinian advocacy spaces, in UN forums, and in countries sympathetic to Palestinian self-determination. It will be deployed repeatedly in international law discussions, in humanitarian advocacy, and in diplomatic negotiations. Israel has sacrificed doctrinal consistency for tactical advantage, a trade-off with long-term diplomatic costs.

Regional Responses and the African Union Position

The regional response to Israel’s Somaliland recognition has been marked by swift and coordinated diplomatic backlash from states perceiving the move as threatening to regional stability and continental legal norms. This response, while framed in terms of principle, also reflects genuine strategic anxieties and legitimate concerns about precedent-setting.

Somalia’s response was immediate and categorical. The government of Somalia, led by President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, joined Egypt, Turkey, and Djibouti in a coordinated statement rejecting Israel’s recognition as a violation of Somaliland’s territorial integrity and Somalia’s sovereignty. The Somali statement reaffirmed “full support for the unity, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Somalia” and condemned what it characterized as Israeli interference in internal Somali affairs. This response carries genuine weight given Somalia’s status as a UN member state and the international legitimacy attending its official positions.

Turkey’s response proved particularly sharp, characterizing the recognition as aligned with Israeli “expansionist policy” and efforts to prevent Palestinian state recognition. Turkish Foreign Ministry statement emphasized that “this initiative by Israel aligns with its expansionist policy and its efforts to do everything to prevent the recognition of a Palestinian state, constitutes overt interference in Somalia’s domestic affairs.” Turkey’s strong response reflects its strategic alliance with Somalia, extensive military presence in the country via the TURKSOM military base, and broader Turkish interests in regional stability.

Egypt’s coordination with Somalia and Turkey reflects strategic considerations regarding the Red Sea, Suez Canal alternatives, and Egypt’s broader position as a regional power dependent on stable neighboring states. Egypt’s Foreign Ministry emphasized that recognition “undermined the territorial integrity of Somalia,” establishing Egypt’s position as defender of state sovereignty principles.

The African Union’s response proved most institutionally significant. AU Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat issued an official statement explicitly rejecting Israel’s recognition and reaffirming “the African Union’s unwavering commitment to the unity and sovereignty of Somalia.” The AU further warned that recognition of Somaliland “risks setting a dangerous precedent with far-reaching implications for peace and stability across the continent.” This warning crystallizes the fundamental AU concern—that Somaliland recognition establishes precedent that could encourage other secessionist movements (Biafra in Nigeria, Western Sahara, Anglophone Cameroon, and others) to seek international validation and external recognition.

The AU’s position rests on the 1964 Organization of African Unity Resolution 16(1), which established the principle of border inviolability as a continental norm. This principle emerged from African states’ recognition that colonial boundaries, drawn without regard to ethnic, cultural, or linguistic realities, created artificial borders. Rather than permitting those borders to be redrawn through secession and state fragmentation, African states collectively chose to freeze borders as they existed at independence. This represented a pragmatic choice to prevent endless border conflicts and state fragmentation but came at the cost of legitimizing arbitrary colonial-era boundaries that often violated national aspirations.

Somaliland represents a potential exception to this principle, yet the AU has consistently refused to grant formal recognition despite Somaliland’s three-decade stability and democratic development. The AU’s reasoning has been that recognizing Somaliland without a negotiated agreement between Somalia and Somaliland would establish precedent for recognizing any separatist movement that achieved de facto control and minimal governance capacity. The AU explicitly warned that if Somaliland achieves recognition through unilateral Israeli action without comparable agreement with Somalia, other secessionist movements would gain legal and political justification to pursue equivalent recognition.

This AU position confronts its own logical vulnerabilities. The AU has already recognized South Sudan’s 2011 independence and Eritrea’s 1993 separation from Ethiopia—both border changes within the continental system. The distinguishing factor appears to be that both South Sudan and Eritrea achieved separation through negotiated agreements (Comprehensive Peace Agreement for South Sudan, agreement with Ethiopia for Eritrea) rather than unilateral declaration. Yet this distinction, while legally coherent, creates an uncertain framework. Somalia has consistently refused any negotiated agreement with Somaliland, rendering it impossible for Somaliland to meet the AU’s implicit standard of negotiated separation. The AU thus positions Somaliland in an impossible situation—it cannot achieve separation through unilateral declaration (rejected by AU), and cannot achieve separation through negotiation (rejected by Somalia).

Djibouti’s participation in the coordinated backlash reflects its strategic interests regarding port competition and Red Sea dominance. Djibouti has historically monopolized as the primary port gateway for landlocked Ethiopia, a position generating substantial revenue for Djibouti’s government. The Somaliland-Ethiopia MOU threatens this monopoly by creating an alternative Red Sea outlet for Ethiopian commerce. Djibouti thus perceives Somaliland’s international recognition as directly threatening its own economic and strategic interests. Additionally, Djibouti has experienced significant tensions with the UAE regarding port development agreements and has accused Abu Dhabi of disguised colonialism through development investment. Djibouti recognizes that UAE support for Somaliland recognition reflects UAE interest in controlling Berbera port and challenging Djibouti’s dominance—creating alignment between Djibouti’s interests and Somalia’s position.

Notably, Ethiopia maintained strategic ambiguity regarding Israel’s recognition, neither endorsing nor condemning the move. Ethiopia, which has signed the Somaliland MOU for Berbera port access, faces a delicate political position. Formal endorsement of Somaliland independence would provoke Somalia, already upset by the port agreement and threatening to withdraw Ethiopian peacekeeping forces from AMISOM. Conversely, condemning Somaliland recognition would undermine Ethiopia’s own strategic investments in the port. Ethiopia’s silence appears designed to permit maintaining both relationships—with Somalia through diplomatic restraint, and with Somaliland through continued implementation of the port MOU without requiring formal independence recognition.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: Drivers and Consequences

The recognition initiates several cascading effects that warrant systematic analysis. These effects operate at multiple levels—bilateral, regional, continental, and global—with varying timescales from immediate diplomatic reactions to long-term institutional changes.

Immediate Effects

The recognition triggers formal diplomatic statements but likely avoids military escalation. Somalia lacks capacity to militarily coerce Somaliland, while international powers have established expectations that Red Sea conflicts remain contained to Houthi attacks on shipping rather than inter-state warfare. However, Somalia may pursue indirect consequences including potential withdrawal of Ethiopian peacekeeping forces from AMISOM (African Union Mission to Somalia), deterioration of Somalia-Ethiopia security cooperation against al-Shabaab, and diplomatic isolation of Israel in AU forums.

Recognition Cascade Dynamics

The recognition establishes a potential domino effect for other countries considering Somaliland recognition. Israel’s status as a UN member country lends weight to its recognition that Taiwan’s 2022 recognition (Taiwan itself lacks UN membership) could not provide. If the Trump administration extends US recognition to Somaliland—a possibility signaled by Republican figures like Senator Ted Cruz and references in Project 2025 policy documents—the cascade effect would intensify substantially. US recognition would provide additional legitimacy, potentially persuading other countries to reconsider positions. However, the cascade is not inevitable. The AU’s opposition, Somalia’s determined diplomatic response, and institutional hesitations within US Africa policy (concerns about destabilizing Somalia, setting precedent for other African secessionist movements, and complications with existing US-Somalia security cooperation) may constrain broader recognition movements.

Port Competition and Regional Power Realignment

The recognition accelerates the transformation of Red Sea port competition. Berbera’s development as a full-fledged commercial and potential military port threatens Djibouti’s historic monopoly as the primary Red Sea gateway. Ethiopia’s Somaliland MOU position is strengthened by Israel’s recognition, as Addis Ababa can now argue it operates within an internationally recognized framework rather than supporting a separatist entity. This could prompt Ethiopia to accelerate implementation of the Somaliland port agreement despite Somalia’s objections. UAE interests are simultaneously advanced and complicated—Berbera port investment gains legitimacy through Israel’s recognition, but also faces potential international law challenges from Somalia and AU opposition that might constrain further investment.

Geopolitical Alignment in the Horn

The recognition reflects and accelerates the bifurcation of Horn of Africa alignment into competing blocs. The Israel-Somaliland-Ethiopia axis, strengthened by the recognition and supported by UAE investment in Berbera, represents a Western-aligned coalition focused on Red Sea access and countering Iranian influence. The Somalia-Egypt-Turkey-Djibouti coalition represents a counter-alignment focused on upholding traditional African state sovereignty principles and protecting Djibouti’s port interests. This alignment pattern resembles broader Trump administration strategy of constructing coalitions based on shared interests rather than ideological alignment or institutional membership—the Abraham Accords paradigm extended into Africa.

Impact on Al-Shabaab and Regional Terrorism

The recognition may inadvertently strengthen al-Shabaab’s recruitment and operational capacity. International Crisis Group assessments noted that the Ethiopia-Somaliland port deal has been weaponized by al-Shabaab to generate recruits by portraying it as foreign violation of Somali sovereignty. The Somaliland recognition intensifies this narrative, allowing al-Shabaab to frame international support for Somaliland as Western-aligned powers fragmenting the Islamic world and supporting Christian-majority Ethiopia against Muslim Somalia. Whether this recruitment impact translates to operational capability remains uncertain, but the recognition provides al-Shabaab with propaganda value and narrative justification.

Palestinian Cause and International Law

The recognition establishes precedent that weakens Israel’s positions regarding Palestinian self-determination. This is not merely rhetorical consequence—it affects voting patterns in UN forums, positions in International Court of Justice proceedings, and framing in Human Rights Council discussions. Palestinian advocacy organizations will systematically reference the Somaliland recognition as evidence of selective application of self-determination principles. This precedent will be deployed in negotiations, international forums, and humanitarian advocacy with measurable diplomatic costs to Israel.

Trump Administration Policy Trajectory

The recognition serves as trial balloon for Trump administration Africa policy. If Trump administration moves toward formal US recognition of Somaliland, it signals the administration’s willingness to restructure African order around strategic interests rather than organizational principles. This would represent significant departure from Biden administration approach (which emphasized AU unity) and signal prioritization of Red Sea access, counter-China positioning, and Abraham Accords expansion over traditional institution-building. Conversely, if Trump administration declines to recognize Somaliland despite Republican advocacy, it suggests hesitation about the precedent-setting costs and indicates institutional constraints within US Africa policy.

The International Law Dimension: Montevideo Convention and African Precedent

Understanding the legal dimensions of Somaliland statehood requires examination of international law standards for state recognition and how those standards have been selectively applied across different contexts.

The Montevideo Convention of 1933 established widely accepted criteria for statehood: defined territory, permanent population, government capacity, and ability to conduct international relations. Somaliland meets or arguably exceeds these standards on most dimensions. The territory encompasses approximately 137,600 square kilometers with defined borders (though Puntland disputes eastern boundaries and recent contested areas along the Sool and Sanaag provinces). The permanent population comprises six million inhabitants with distinct cultural and linguistic characteristics. Somaliland possesses a functioning government with separation of powers, elected leadership, bureaucratic capacity, and security forces. The territory conducts international relations through de facto diplomatic offices in multiple countries, signed agreements with foreign states (Ethiopia MOU, DP World concession, UAE investments), and participation in regional bodies.

Yet international law scholars debate whether the Montevideo Convention criteria constitute necessary and sufficient conditions for recognition or merely guidance. The critical distinction involves the difference between objective statehood (whether an entity meets criteria making it a state in fact) and recognition (the political-diplomatic process through which states acknowledge statehood). International practice reveals that entities meeting Montevideo criteria may remain unrecognized for decades, while recognition decisions reflect political calculation rather than objective legal assessment.

The African Union’s invocation of border inviolability represents a continental legal norm that supersedes application of the Montevideo Convention in the African context. In 1964, African states collectively chose to prioritize stable borders over redrawn boundaries that might reflect ethnic or cultural boundaries more accurately. This choice reflected recognition that colonial boundaries created multi-ethnic states with limited legitimacy but that redrawing those boundaries would generate endless conflicts. The AU established that recognition requires either negotiated agreement with the parent state or achievement of independence through armed conflict resulting in actual state separation. Somaliland’s case fits neither criterion—Somalia refuses negotiation, and while Somaliland fought for independence through the civil war, it achieved separation through state collapse rather than through direct Somaliland-Somalia conflict.

The two African precedents for border change (Eritrea 1993, South Sudan 2011) both involved negotiated agreements. Eritrea fought Ethiopia and achieved de facto separation through armed conflict, followed by referendum endorsed by Ethiopian government under Mengistu Haile Mariam’s successor. South Sudan was created through the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between Sudan’s government and SPLM/A, formalized by referendum. Neither involved unilateral declaration without parent state agreement. Somaliland’s 1991 declaration occurred within the context of complete Somali state collapse, raising the question of whether Somalia’s absence of functioning government effectively released Somaliland from negotiation requirements.

Israel’s recognition argument implicitly relies on the distinction between objective statehood and recognition. By recognizing Somaliland, Israel asserts that Somaliland has achieved such complete de facto statehood that recognition merely acknowledges existing reality rather than creating new legal categories. Foreign Minister Sa’ar emphasized that recognition acknowledges Somaliland’s three decades of functioning government, stable borders, and peaceful power transfers. This position treats recognition as declaratory (recognizing what already exists) rather than constitutive (creating new legal entities through recognition act).

However, this argument faces substantial challenge from the principle of legal effectiveness. In international law, recognition possesses constitutive dimensions regardless of its conceptualization—once Israel recognizes Somaliland, international legal implications follow even if Israel intended mere acknowledgment. Somaliland gains capacity to sign treaties, conduct diplomatic relations, and make international claims in ways previously impossible. Recognition thus creates legal change even if conceptually presented as acknowledgment.

The AU’s concern that Somaliland recognition establishes precedent for other secessionist movements contains legitimate legal foundation. Once recognition occurs without parent state agreement, the bar is lowered for other separatist entities. Biafra, despite significant autonomy, never achieved comparable democratic development and stable governance as Somaliland. Yet if Somaliland recognition succeeds through Israeli initiative despite AU opposition, advocates for Biafran independence could invoke the precedent to argue their case. The AU’s fear of cascading recognitions reflects genuine legal concern, not merely political calculation.

Future Implications and Trajectories

The recognition initiates several potential futures depending on how regional powers and the Trump administration respond. Understanding these trajectories requires examining both optimistic and pessimistic scenarios regarding consolidation or unraveling of the recognition’s effects.

Scenario One

Trump Administration Recognition and Cascade Effects. If the Trump administration follows Israel’s precedent with US recognition of Somaliland, the cascade effect would intensify substantially. US recognition would carry greater diplomatic weight than Israeli recognition alone, particularly regarding AU credibility, World Bank and IMF relationships, and integration into international institutions. A US recognition decision would likely trigger other countries—particularly Gulf states and other Abraham Accords members—to consider recognition. Ethiopia would face reduced costs for formal recognition given international precedent. Within months, Somaliland could transition from unrecognized separatist entity to de facto international state with multiple recognizing powers. This scenario would fundamentally alter Red Sea geopolitics, strengthen Ethiopia’s port alternatives to Djibouti, and accelerate the Abraham Accords expansion into Africa. The costs would include AU institutional weakness, potential Somalia-Ethiopia security cooperation breakdown, al-Shabaab recruitment bolster, and strengthening of accusations regarding Israeli hypocrisy on Palestinian statehood.

Scenario Two

Isolated Israeli Recognition Without Cascade Effects. Conversely, if Trump administration maintains strategic distance from formal Somaliland recognition despite receptiveness to the concept, Israel’s recognition could remain an isolated diplomatic anomaly. Other countries might maintain de facto relationships without formal recognition. The AU’s institutional authority would be preserved, Somalia’s territorial claims would retain international legal backing, and the formal international system’s stability mechanisms would remain intact. This scenario would disappoint Somaliland leadership, reinforce the utility of international recognition as a genuine political constraint, and limit red Sea power realignment. However, it would also mean Israel’s recognition carries limited consequence—Israeli embassies in Hargeisa and Somaliland embassies in Tel Aviv would exist but lack the institutional integration and economic benefits that cascade recognition would provide.

Scenario Three

Regional Conflict Escalation. A third possibility involves Somalia attempting to escalate the Somaliland dispute through proxy conflict, military mobilization, or Ethiopia-Somalia confrontation over the port agreement. Should Somalia withdraw Ethiopian peacekeeping forces, al-Shabaab could exploit security vacuums to expand territorial control. A Somalia-Ethiopia military confrontation, while unlikely, remains within the realm of possibility if Somalia perceives existential threat to territorial integrity. This scenario would destabilize the entire Horn region, trigger humanitarian crises, and force international attention toward conflict resolution. However, the absence of active military conflict for over a decade suggests both Somalia and Ethiopia prefer to avoid direct confrontation despite mutual tensions.

Scenario Four

Palestinian Statehood Advancement. An unanticipated consequence of Somaliland recognition could involve acceleration of Palestinian statehood discussions in international forums. As Palestinian advocates invoke the Somaliland precedent to argue for Palestinian recognition, international pressure may build for recognizing Palestinian state status. This could occur through UN General Assembly declaration, international court proceedings, or expanded bilateral recognitions. The hypocrisy charge creates vulnerability for Israel if the Trump administration does not simultaneously address Palestinian statehood questions. This scenario would represent recognition of Palestinian self-determination as consequence of Israel’s Somaliland recognition—an ironic inversion where Israeli strategic move inadvertently strengthens Palestinian diplomatic hand.

The Most Probable Path

Based on available evidence, the most likely trajectory involves partial cascade effects without comprehensive shift in international order.

The Trump administration will likely signal receptiveness to Somaliland recognition while delaying formal action pending clarification of benefits and internal policy consensus.

Ethiopia may gradually move toward formal recognition once international precedent is further established.

Some Gulf states and other Abraham Accords members may follow Israel’s lead.

The AU’s opposition will prevent comprehensive institutionalization of Somaliland within the international system—UN membership will remain blocked, World Bank access will remain constrained, and formal legal standing will remain contested.

Somaliland will achieve partial internationalization—recognized by a coalition of states but opposed by continental organization—positioning it as a quasi-state with hybrid status comparable to Northern Cyprus or Kosovo.

Red Sea port competition will intensify, benefiting Berbera development but not transforming it into dominant hub.

Palestinian advocacy will systematically leverage the Somaliland precedent but without producing immediate Palestinian statehood recognition.

Future Steps and Recommendations for Stability

The international community faces several imperative steps to manage the consequences of Israel’s recognition and orient outcomes toward regional stability and respect for international law.

The fundamental challenge involves reconciling two competing principles: support for Somaliland’s genuine democratic development and stability with preservation of international order principles regarding border inviolability and sovereign integrity. Ignoring either principle produces instability and injustice. The pathway forward requires creative diplomacy transcending the binary choice between Somaliland independence or perpetual non-recognition.

The most constructive option involves facilitating genuine Somalia-Somaliland negotiation through international mediation aimed at producing a negotiated agreement comparable to the Eritrea or South Sudan models. Such negotiation would likely result not in Somalia’s full acceptance of Somaliland independence but rather in recognition of substantial autonomy, confederation arrangements, federal configurations, or federated statehood within a broader Somali framework. Djibouti attempted to facilitate such talks in late 2023, but negotiations stalled when Somaliland subsequently signed the Ethiopia port MOU.

Renewed mediation efforts, potentially through the AU, UN, or regional organizations, could refocus negotiations on mutual benefits and constitutional arrangements acceptable to both parties.

Regional powers—Ethiopia, Egypt, Turkey, and Djibouti—should establish mechanisms for coordinating Red Sea security and port access without requiring Somaliland independence as prerequisite. Current tensions reflect competition for port access that could be managed through joint development agreements, port zone sharing, and coordinated security arrangements that preserve Somalia’s formal territorial sovereignty while acknowledging Somaliland’s de facto autonomy. The Ethiopia-Somaliland MOU model could be expanded into a broader Horn of Africa framework managing maritime access and commerce without necessitating political boundary changes.

The Trump Rapid Recognition should resist the temptation to recognize Somaliland too quickly, absent a significant strategic gain. The Red Sea access Israel obtains through Socan can be operationalized without requiring reion to operationalize.

The Abraham Accords framework can accommodate Somaliland without formal US state recognition, maintaining institutional flexibility and preserving US relationship with Somalia. Delaying US recognition while maintaining Somaliland cooperation provides strategic advantages without incurring the diplomatic costs of challenging AU institutional authority.

The AU must acknowledge the genuine legitimacy of Somaliland’s democratic development and institutional achievements while maintaining border inviolability principles. This might involve establishing new categories for international engagement with non-recognized entities, creating mechanisms for representing unrecognized statelets in AU deliberations, or establishing standards by which entities could achieve recognition through demonstrated governance excellence. Such institutional innovation would provide pathway for Somaliland while constraining precedent for destabilizing secessionist movements.

Israel must acknowledge the fundamental hypocrisy of its Somaliland recognition and Palestinian position, either by reconsidering Palestinian statehood or reconsidering Somaliland recognition. Diplomatic credibility depends on consistency. If Israel genuinely believes in self-determination principles, it must apply them equitably. The alternative—maintaining both positions—will result in progressive credibility erosion and weaponization of the contradiction in every international forum addressing Palestinian issues.

Palestinian and Palestinian-supporting states should leverage the Somaliland precedent to advance statehood claims in international forums. The precedent is now established and documented—Israeli recognition of Somaliland on self-determination grounds must logically extend to Palestinian statehood. This argument possesses force precisely because it exposes the contradiction in Israeli positions. Rather than viewing Somaliland recognition as purely negative, Palestinian advocates can frame it as establishing legal justification for Palestinian statehood claims.

Conclusion

Stability, Sovereignty, and the Crisis of Consistency

Israel’s December 26, 2025 recognition of Somaliland as an independent state marks a significant inflection point in Horn of Africa geopolitics, international legal precedent, and the consistency of diplomatic positioning on self-determination and territorial sovereignty. The decision reflects genuine strategic imperatives—Red Sea access, counter-Iran positioning, Abraham Accords expansion—pursued by Israeli leadership through sophisticated intelligence operations and diplomatic channels.

Yet the recognition simultaneously establishes a fundamental contradiction between Israeli positions on Somaliland independence and Palestinian statehood that cannot be reconciled through reframing or doctrinal argument. Israel has now formally acknowledged that self-determination principles can justify separation from parent states without parent state consent, that stable governance and democratic institutions constitute legitimate bases for statehood recognition, and that regional strategic interests justify extending recognition to entities meeting these criteria. These principles, logically extended, establish foundation for Palestinian statehood claims that Israeli government has consistently opposed.

The regional consequences will unfold across multiple timescales. Immediate effects involve diplomatic backlash from Somalia, Egypt, Turkey, and the AU, establishing political cost for the recognition. Medium-term effects include potential cascade of recognitions if Trump administration follows Israel’s precedent, creating bifurcated international positions on Somaliland with some countries recognizing and others opposing. Long-term consequences involve either stabilization of Somaliland as a quasi-state with hybrid international status comparable to Kosovo or Cyprus, or escalating conflict as Somalia attempts to reassert control over separatist regions.

The Palestinian dimension carries particular significance because it demonstrates that recognition decisions reflect political calculation rather than consistent application of legal principles. Israel prioritized strategic advantage over doctrinal consistency, sacrificing credibility in international forums dedicated to Palestinian self-determination. This trade-off may prove strategically valuable for Israel in the short term but will exact long-term diplomatic costs through systematic weaponization of the contradiction.

The international community must navigate this moment with recognition that stability, respect for sovereignty, and self-determination principles are not identical interests that can be simultaneously maximized. Rather, they represent competing values requiring negotiated balancing through diplomatic creativity rather than rigid adherence to zero-sum positions. Somaliland’s genuine democratic achievements and stability merit international acknowledgment without necessarily requiring formal state independence. Equally, Palestinian self-determination aspirations merit support without requiring adoption of positions contradicting those extended to Somaliland.

The path forward requires transcending the binary choice between Somaliland independence and perpetual non-recognition toward negotiated arrangements acknowledging Somaliland’s distinct identity and governance capacity while preserving broader Somali territorial framework. Such arrangements—whether confederation, federation, or enhanced autonomy—would recognize Somaliland’s achievements while constraining precedent for destabilizing secessionist movements throughout Africa.

Israel’s recognition serves as catalyst for this conversation rather than endpoint. The essential work of regional stabilization, respect for sovereignty, and promotion of self-determination through peaceful mechanisms remains ahead. The international community’s response to Somaliland recognition will establish patterns for managing territorial disputes, secessionist movements, and competing claims throughout the twenty-first century. The moment demands wisdom, consistency, and commitment to principles transcending immediate strategic interest.