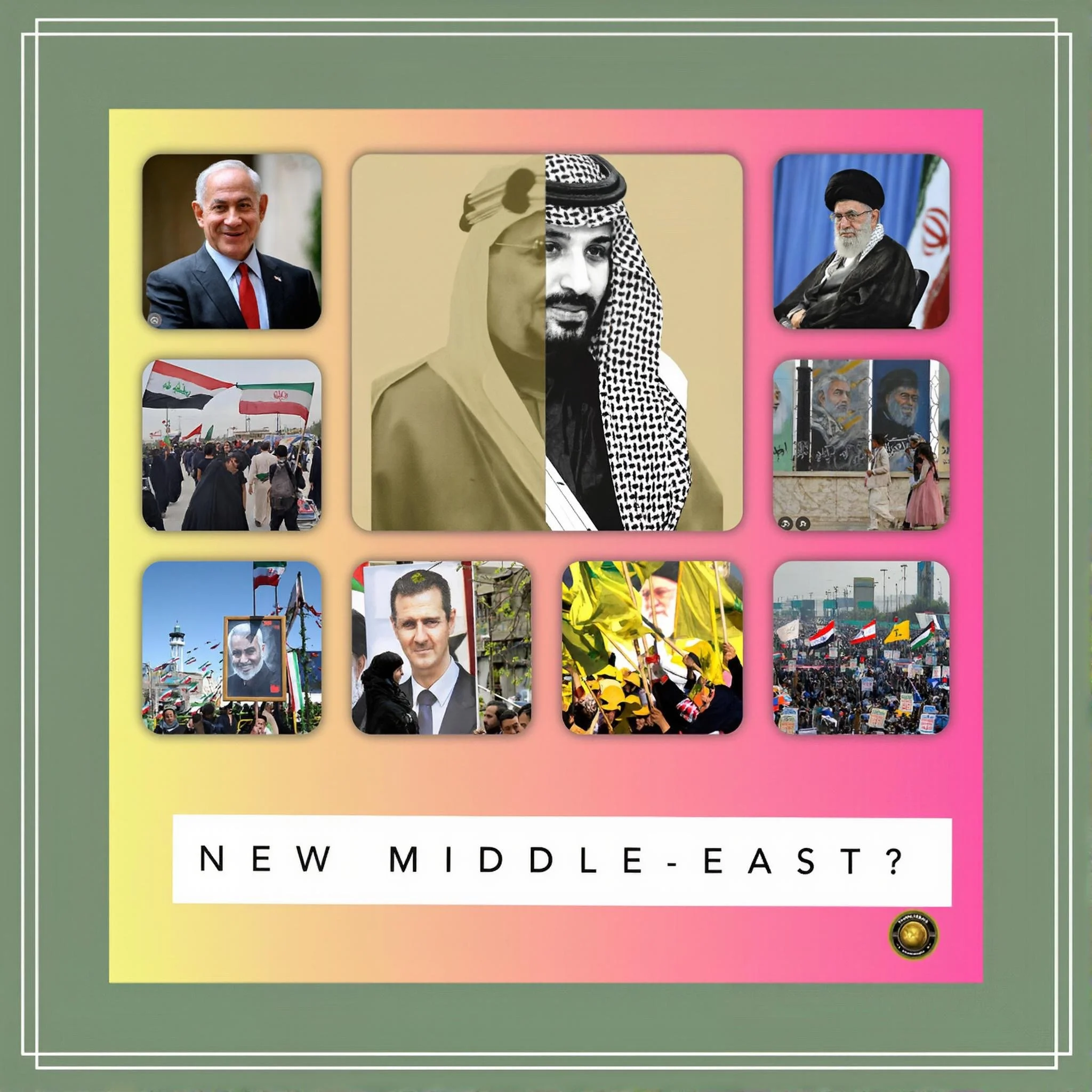

Iran’s Axis Falls: Is Sectarianism Set to Rise from the Ashes? The Next Chapter in the Middle East

Executive Summary

The Next Phase of Shiite Politics in a Post-Axis Middle East

The Iranian-led “Axis of Resistance” that dominated regional geopolitics from the 2003 American invasion of Iraq through 2023 has been substantially dismantled by successive Israeli air campaigns, the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria, and the decimation of key proxy organizations, including Hamas, Hezbollah, and various Iraqi militias.

Israeli operations launched between September and December 2024 reduced the axis from a functioning transnational network to a collection of severely weakened, territorially constrained organizations.

The October 2024 Israeli strikes on Iran itself degraded Tehran’s air defense capabilities and missile production facilities to an extent that American assessments suggest at least one year of reconstitution would be required before Iran could resume production of ballistic missiles.

Simultaneously, the December 2024 fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria eliminated the critical land corridor through which Iran had supplied arms and resources to Hezbollah, fundamentally disrupting the logistics that had enabled the axis to function as a coordinated network.

Yet conventional analysis suggesting that the axis’s destruction necessarily implies the dissolution of sectarian politics in the Middle East fundamentally misunderstands the nature of Shiite political identity and the underlying social structures that sustained the axis throughout its existence.

Rather than operating solely through state-to-state relationships or centralized command structures originating in Tehran, the axis relied upon transnational networks of faith, community, and family ties binding Shiite populations across borders, combined with shared confrontation against Sunni extremism and Israeli power.

These underlying structures remain substantially intact even as the military and state apparatus of the Axis has been devastated.

The critical question animating Middle Eastern geopolitics in the future is therefore not whether the axis of resistance can be reconstituted—it likely can, albeit in weakened form—but rather how regional powers including Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Israel will address the persistent reality of Shiite identity and the communities animated by that identity across Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen, and the broader Levant.

Introduction

Twilight of the Shiite Crescent

The concept of the “Axis of Resistance” emerged from the American invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the strategic vacuum that followed the rapid collapse of Saddam Hussein’s regime.

In the aftermath of the invasion, Iran capitalized on the turmoil engendered by the removal of its principal regional adversary to construct what would become the most ambitious transnational network of aligned states and non-state actors assembled in the Middle East since the end of the Cold War.

The network encompassed the Syrian government under Bashar al-Assad, the Lebanese organization Hezbollah, various Shiite militias operating in Iraq, the Houthis in Yemen, and eventually Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza. By 2014, analysts regularly observed that Iran effectively controlled four Arab capitals: Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus, and Sanaa.

This extraordinary concentration of influence represented not merely a demonstration of Iranian military and financial power, but rather a sophisticated exploitation of transnational identities, sectarian grievances, and religious networks that bound Shiite communities across the region.

King Abdullah of Jordan captured the Western anxiety animating this development when he referred ominously to the emerging “Shiite crescent” stretching from Iran through Iraq and Syria into Lebanon—a formulation suggesting that sectarian religious identity might reshape the fundamental political geography of the Middle East.

Yet the axis’s apparent dominance and reach obscured fundamental vulnerabilities rooted in its dependence upon aging Iranian leaders, the fragility of the Syrian regime, the limitations of proxy organizations lacking conventional state resources, and the enduring friction between Iranian and Arab nationalism.

The October 7, 2023, Hamas attack on Israel and the subsequent Israeli campaigns against Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, and Iran itself exposed these vulnerabilities with devastating clarity. Rather than serving as a deterrent preventing Israeli military action—the role Iran had envisioned for the axis—the network instead became a focal point for Israeli military targeting that resulted in the destruction of capabilities Iran had spent decades accumulating.

By the conclusion of 2024, the axis had been militarily decimated, its organizational structures disrupted, its leaders assassinated or scattered, and its principal state supporter in Syria effectively removed from the geopolitical map.

Yet despite this destruction, many analysts and regional observers note with concern that the underlying conditions that gave rise to the axis—sectarian identities, Shiite grievances, transnational religious networks, and the concentration of Shiite populations in territories perceived as strategically important—remain substantially unchanged.

The question animating the current phase of Middle Eastern geopolitics is therefore whether the axis represents a temporary historical phenomenon permanently shattered by Israeli military power, or rather a surface manifestation of deeper structural forces rooted in sectarian identity and community that will persist and potentially reconstitute themselves in new organizational forms.

The answer to this question appears to be that the axis, in its formal configuration as an integrated network of state and non-state actors coordinated from Tehran, is unlikely to be fully reconstituted.

Yet the sectarian identities, family networks, religious commitments, and community bonds that sustained the axis will almost certainly outlast the military and political structures that housed them, creating conditions for the emergence of new Shiite-centered political movements and organizations even if the specific historical configuration of the current axis does not persist.

Key Developments: The Dismantling of the Axis, 2023-2025

Axis Destroyed, Identity Endures: The Persistence of Shiite Power Networks

The unraveling of the Axis of Resistance unfolded through a series of military, political, and organizational catastrophes that compressed into little more than two years events that might otherwise have taken decades.

The initiating event, the October 7, 2023, Hamas attack on Israel, triggered a cascade of consequences that were neither intended nor anticipated by the architects of the axis.

While Hamas’s assault demonstrated the continued capacity of Palestinian militant organizations to inflict casualties on Israeli civilians, the subsequent Israeli response proved catastrophic for the broader axis network.

Israel’s war in Gaza, lasting through the following twelve months, not only devastated Palestinian civilian infrastructure but also demonstrated that the axis’s supposedly integrated military coordination had failed to provide adequate support for its Palestinian component.

The coordination room that Iran had established to ensure unified action among Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Hezbollah, Iraqi militias, and the Houthis proved unable to generate effective mutual support in ways that deterred Israeli military action.

The first decisive blow against the axis came in January 2024 when Israeli airstrikes assassinated Saleh al-Arouri, the deputy chairman of Hamas’s political bureau, at his residence in Beirut.

This operation, occurring on Lebanese territory and targeting the political and strategic leadership of a Palestinian organization, represented a dramatic escalation in Israeli operational reach.

The killing of al-Arouri severed the connection between Hamas’s political leadership in the Levant and its operational command in Gaza, contributing to the fragmentation of Hamas’s leadership structure that would accelerate throughout 2024.

Subsequent Israeli operations would target additional senior Hamas leaders including Ismail Haniyeh, whose assassination in Tehran in July 2024 represented an extraordinary penetration of Iranian territory and intelligence that humiliated the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

The intensification of the Israeli-Hezbollah conflict beginning in September 2024 delivered the most concentrated blow to the axis’s military capabilities.

On September 17, 2024, Israeli operations detonated exploding pagers and walkie-talkies distributed throughout Hezbollah’s operational networks, resulting in approximately 12 deaths and over 2,750 wounded, with approximately 1,500 fighters rendered temporarily or permanently unable to participate in combat operations.

Dozens of Hezbollah members suffered blindness or loss of limbs, while the psychological impact of an adversary capable of infiltrating Hezbollah’s communication networks created severe disruption of organizational command and control.

The subsequent assassination of Hezbollah’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah on September 27, 2024, along with his successor Hashem Safieddine in October, eliminated the organizational leadership that had held the group together for three decades.

Israeli airstrikes subsequently destroyed Hezbollah’s missile stockpile, dismantled the group’s southern Lebanese military infrastructure, and displaced over 111,000 Lebanese civilians fleeing the conflict zone.

The collapse of the Assad regime in Syria on December 8, 2024 represented perhaps the most strategically significant blow to the axis. The swift fall of the Assad family’s five-decade dictatorship eliminated the critical land corridor that had connected Iran to Hezbollah and Palestinian organizations in the Levant.

This corridor had been essential to Iran’s ability to transfer weapons, ammunition, and supplies to its allies.

The new Syrian government, dominated by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, a Sunni Islamist organization historically hostile to Iran, represented a fundamental reorientation of Syria’s international alignment.

The loss of Syria meant that Iran could no longer rely on a critical waypoint for logistics, eliminated the potential for joint military coordination with Syrian forces, and created a territorial gap through which Israeli and Turkish forces could operate with substantially reduced constraint.

Concurrently, Israel conducted unprecedented air campaigns against Iranian territory itself. The October 26, 2024 operation designated “Days of Repentance,” involving over 100 Israeli aircraft traveling 2,000 kilometers to strike 20 targets across Iran, represented the largest Israeli air operation against Iran since the establishment of the Islamic Republic.

The strikes targeted air defense batteries, unmanned aerial vehicle factories, and ballistic missile production facilities.

American assessments subsequently concluded that the strikes had crippled Iran’s missile production capability, with estimates suggesting that at least one year would be required for Iran to reconstitute the production capacity destroyed in the operation.

An Iranian news agency associated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps confirmed that military installations in western and southwestern Tehran, as well as bases in Ilam and Khuzestan provinces, had been attacked.

The psychological impact of Israel’s ability to penetrate deep into Iranian territory, strike critical military installations, and depart without loss proved significant in conditioning regional perceptions of Iranian invulnerability.

Throughout 2024-2025, additional organizational collapse accelerated the axis’s disintegration.

Hamas’s Gaza-based leadership was substantially eliminated through Israeli operations, with survivor leaders scattering to Qatar, Turkey, and Egypt. Iraqi Shiite militias, while maintaining substantial organizational presence, faced the withdrawal of American forces from Syrian territory, which disrupted their ability to coordinate with counterparts in Syria and Lebanon.

The Houthis, while continuing sporadic attacks on Red Sea shipping and maintaining rhetorical commitment to supporting Palestinian resistance, faced degraded capabilities following Israeli strikes and appeared to reduce operational tempo beginning in November 2025.

The overall effect was the transformation of a network that had functioned as a somewhat coordinated strategic alliance into a collection of territorially constrained, organizationally damaged, and mutually isolated groups lacking clear strategic direction or reliable means of coordination.

Facts and Concerns: The Military and Organizational Devastation

Shattered Alliances, Unbroken Communities

The destruction inflicted upon the Axis of Resistance entities represents an unprecedented degradation of capabilities assembled over decades.

Hamas, which had controlled Gaza since 2007 and possessed an organized military force estimated at 40,000-50,000 fighters at the beginning of 2024, faced complete destruction of its command and control infrastructure, assassination of senior leaders, and elimination of an estimated 17,000-25,000 fighters during the 2024 Israeli military campaign.

The organization’s capacity to generate military resistance or govern territory was substantially reduced, with surviving elements dispersed across the region under conditions of extraordinary constraint.

Palestinian Islamic Jihad, a smaller component of the Palestinian resistance, was similarly decimated, with much of its senior leadership eliminated and its operational capability substantially reduced.

Hezbollah’s transformation from a unified military-political organization into a fragmented force represents perhaps the most dramatic organizational collapse.

The organization had maintained an estimated 130,000-150,000 fighters distributed across a formal military structure, political party apparatus, and social service networks providing education, healthcare, and welfare services to Lebanon’s Shiite population.

The 2024 Israeli campaign reduced Hezbollah’s immediate operational capacity by thousands of fighters, destroyed the vast majority of its missile stockpile, and degraded its air defense and logistical infrastructure.

The assassination of the organization’s senior leadership, combined with the displacement of Lebanese Shiite civilians from southern Lebanon, disrupted the social base upon which Hezbollah relied for recruitment and support.

Estimates suggested that Hezbollah would require years to reconstitute capabilities destroyed in months of Israeli military operations.

Iranian air defense capabilities suffered unprecedented degradation during the October 2024 strikes. Pre-strike assessments identified approximately 200 Iranian air defense systems distributed across the country in layers designed to protect against sustained air attacks.

The October 26 operation reportedly destroyed or severely damaged approximately 10-15 percent of Iran’s air defense capacity, while American assessments suggested that losses of more sophisticated systems including S-300 and S-400 units would require 12-24 months for reconstitution through Russian supply or domestic production.

The remaining air defense systems operated in a degraded state, with maintenance challenges and supply shortages limiting operational effectiveness. This degradation left Iran substantially more vulnerable to future Israeli military operations than at any time since the Islamic Republic’s establishment.

Iraqi Shiite militias, while maintaining organizational presence and some operational capacity, faced the withdrawal of American forces from Syria in December 2024, the loss of the Syrian land corridor, and growing tensions between militia factions and the Iraqi Coordination Framework government.

The Popular Mobilization Forces, the umbrella organization encompassing most Iranian-aligned militias, experienced political fracturing as constituent organizations pursued increasingly independent strategies.

Major organizations including Kataib Hezbollah and Asaib Ahl al-Haqq faced American sanctions, Iraqi government pressure for disarmament and integration into formal security forces, and constraints on cross-border operations imposed by loss of Syrian bases.

While these groups maintained capacity for localized operations and political influence within Iraq, their ability to operate as components of a broader regional network was substantially constrained.

Yet despite this military and organizational devastation, informed observers note with concern that the underlying Shiite communities from which these organizations emerged have not been destroyed.

The vast majority of Hezbollah’s social service apparatus, including schools, hospitals, and welfare organizations, remain operational even after military defeats. Shiite communities in Lebanon, Iraq, and Yemen continue to constitute substantial populations animating the political systems of these states.

Iraqi Shiites, numbering approximately 15-17 million and constituting roughly 50 percent of Iraq’s population, remain the dominant demographic group in most southern Iraqi provinces and retain substantial political influence through their representation in parliamentary and security structures.

These demographic and social realities suggest that even dramatically weakened military organizations can potentially reconstitute themselves if the political and communal foundations supporting them remain intact.

Cause and Effect: Understanding Sectarian Identity and Transnational Networks

Beyond the Battlefield: Sectarian Identity After the Axis

The deeper cause of the Axis of Resistance’s emergence and resilience lay not primarily in state coordination or military organization, but rather in the mobilization of transnational Shiite identity triggered by the American invasion of Iraq and the subsequent emergence of anti-Shiite militancy in the form of Al-Qaeda affiliates and eventually the Islamic State.

The invasion of 2003 eliminated Iraq’s Sunni-dominated Baathist regime and opened political space for the emergence of Shiite-majority representation in Iraq’s new democratic structures.

This shift in Iraq’s political balance, perceived by Sunni-majority Arab states and Sunni-dominated organizations as an alarming reversal of historical subordination, triggered a sectarian reaction.

The rise of Al-Qaeda in Iraq and its explicit targeting of Shiite civilians, culminating in the bombing of the al-Askari mosque in Samarra in February 2006, initiated a sectarian civil war within Iraq that would claim hundreds of thousands of lives and establish sectarian identity as the primary organizing principle of Iraqi politics.

Iran, recognizing this moment of opportunity and Shiite vulnerability, invested enormous resources—financial, military, and organizational—in supporting Shiite militias defending Shiite communities against Sunni militant attacks.

The networks that emerged during this period—including organizations like the Mahdi Army led by Muqtada al-Sadr, the Badr Corps, and various smaller militias—became the foundation upon which Iran would build its transnational axis.

These organizations, while receiving Iranian support and direction, also maintained strong roots in Shiite communities, drew recruits from local populations seeking to defend their families and neighborhoods, and justified their existence through reference to religious obligation to protect the faith and its adherents.

Over subsequent years, this local foundation was complemented and eventually dominated by transnational sectarian identity.

Shiite networks connected Lebanon’s Shiite communities, dominated by Hezbollah, to Iraq’s Shiite militias, to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and to Shiite populations dispersed throughout the Gulf region.

These transnational connections operated through multiple mechanisms simultaneously. Religious connections linked Shiite communities to the hawzas (religious seminaries) in Najaf and Karbala, where young Shiites from across the region studied Islamic law and theology under grand ayatollahs including Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani.

These educational networks generated long-term relationships, theological frameworks emphasizing Shiite identity and obligations, and personal connections between religious leaders and followers.

The defense of Shiite shrines emerged as a particularly powerful mobilization mechanism. The shrine of Sayyida Zainab in Damascus, believed by many Shiites to be the burial place of the Prophet Muhammad’s granddaughter Zainab, became a focal point for Shiite military mobilization in Syria.

Iraqi, Lebanese, Afghan, and Pakistani Shiites traveled to Syria to defend the shrine against Sunni militant organizations, creating shared experiences of military sacrifice and religious devotion.

This mobilization occurred with explicit Iranian support and coordination, but also with the genuine religious convictions of participants who viewed themselves as engaged in a sacred duty to defend Shiite holy places.

Transnational identity formed through these experiences, reinforced through social media and Shiite satellite television channels that disseminated narratives of Shiite victimization and heroism.

The effect of these transnational sectarian networks was to create conditions in which state-level coordination organized by Iran could function effectively.

Iranian Revolutionary Guard officers could operate in Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria not as foreign occupiers but as participants in a shared Shiite project. Resources flowed through networks animated by both state interest and genuinely transnational religious identity.

Military organizations maintained discipline not merely through state command and control but also through ideological conviction rooted in sectarian identity and religious belief.

When the axis appeared to be at its peak in 2014-2020, with Iran effectively controlling four Arab capitals and projecting power from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, this capacity rested on the combination of Iranian state resources with pre-existing Shiite transnational networks.

The cause of the axis’s current collapse, therefore, does not lie in the simple destruction of military capacity, though that is certainly part of the picture.

Rather, it lies in the combination of military devastation with the sudden loss of critical state partners (Assad’s Syria), the decimation of the organizational leadership that coordinated the network (Nasrallah, al-Arouri, Haniyeh), and the constraint of Iranian capacity to project power through both conventional military means (degraded air defenses, damaged missile production) and logistics (loss of the Syrian corridor).

The effect is not that Shiite identity has been destroyed or that transnational Shiite networks have ceased to exist, but rather that the specific organizational and strategic mechanisms through which Iran had mobilized these networks have been severely disrupted.

The Iran-Saudi Rapprochement and Its Complicated Effects

Tehran’s Lost Crescent: The Collapse and What Comes Next

The signing of the Chinese-mediated Iran-Saudi normalization agreement in March 2023 was widely interpreted as signaling the beginning of the end of the sectarian competition that had animated the axis’s rise.

Saudi Arabia’s decision to reestablish diplomatic relations with Iran after severing ties in 2016 suggested that the fundamental great power competition between the Sunni kingdom and Shiite Iran might be moderating.

The agreement created hopes that Iranian support for Shiite proxies might diminish and that regional states might find mechanisms for managing sectarian competition through diplomatic rather than military means.

Yet the actual effects of the normalization agreement proved more complicated than these initial expectations suggested. While Saudi Arabia and Iran reduced direct military confrontation and initiated diplomatic engagement, the underlying sectarian tensions that had driven their competition persisted.

Saudi Arabia continued to view Iran’s transnational Shiite networks as inherently threatening to Saudi interests, particularly regarding Bahrain, where a Shiite majority has long been governed by a Sunni autocracy facing periodic pressure for political change.

Iranian leaders continued to view support for Shiite communities and organizations as a core component of Iran’s regional strategy and ideological identity.

The normalization agreement moderated certain aspects of competition while leaving fundamental strategic divergences unresolved.

The complicating factor emerged when the axis partners themselves perceived the Iran-Saudi rapprochement as reducing support for their struggle.

Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Houthis interpreted the agreement as potentially signaling Iranian willingness to accommodate Saudi and Gulf Arab interests at the expense of resistance against Israel.

This perception contributed to what some analysts describe as the organizations’ own strategic miscalculation that they could adopt more confrontational postures toward Israel without triggering the kind of overwhelming Israeli military response that materialized in 2024.

The normalization agreement thus paradoxically may have contributed to the very conditions that subsequently decimated the axis, by creating space for Israeli military action that Saudi Arabia and Gulf Arab states, engaged in rapprochement with Iran, were less inclined to actively oppose.

The Persistence of Sectarian Identity Beyond Organizational Structures

From Baghdad to Beirut: The Dissolution of Iran’s Shadow Empire

The fundamental analytical challenge posed by the axis’s collapse centers on distinguishing between the temporary organizational forms in which sectarian identity has been mobilized and the underlying sectarian identity itself.

The Shiite identity that animated the axis rests on theological beliefs distinguishing Shiite Islam from Sunni Islam, on historical narratives of Shiite victimization and noble resistance, on family and kinship connections linking Shiites across national boundaries, and on the economic and social institutions (schools, hospitals, charitable organizations) that Shiite-affiliated organizations have built in communities where Shiites constitute the majority or substantial minority populations.

These deeper foundations appear substantially more durable than the specific military and political organizations that have been devastated in 2024-2025.

The social base of Hezbollah, while damaged by Israeli military operations and the displacement of Lebanese Shiites from southern Lebanon, retains significant capacity for regeneration.

The organization has provided educational, healthcare, and welfare services to Lebanon’s Shiite population for decades, creating organizational infrastructure and psychological loyalty that extends well beyond military combat.

While the organization’s capacity to conduct large-scale military operations has been degraded, its capacity to maintain social services and provide identity and meaning to Lebanese Shiite communities appears likely to persist.

A comparable dynamic applies to Iraqi Shiite militias, which maintain significant roots in Shiite communities throughout southern and central Iraq, draw recruits from local populations motivated by sectarian and national identity, and provide security services and economic opportunities that populations value.

The transnational Shiite public sphere, mediated through satellite television, social media, and networks of religious scholars, has proven itself capable of sustaining narratives that bind distant Shiite communities together.

The defense of Shiite shrines, the celebration of Ashura and other sectarian religious observances, the dissemination of narratives about Shiite victimization and resistance—all of these mechanisms of identity construction appear to have survived the military defeats of 2024 largely intact.

Young Shiites in Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen, and the Gulf continue to be socialized into religious and sectarian identities that emphasize their connection to a broader transnational Shiite community.

This socialization operates partly through formal institutions (religious schools, hawzas) and partly through informal mechanisms (family narrative, community celebration, social media consumption).

The distinction between the axis of resistance as a specific organizational and strategic construct versus sectarian identity as a broader phenomenon appears critical for assessing the region’s future trajectory.

The axis, as an integrated network of state and non-state actors coordinated from Tehran and encompassing governments and militias across the Arab world, appears unlikely to be fully reconstituted in its previous form. Assad’s fall makes Syrian participation in such a network impossible in the medium term.

Hezbollah’s degradation and the displacement of Lebanese Shiites constrains Lebanon’s role. Hamas’s destruction and the decimation of its leadership eliminates Palestinian representation.

Iraqi militias’ increasing independence from Iranian direction and their subordination to Iraqi state authorities limits Iraq’s integration into a Tehran-directed network.

Yet the conditions that generated the axis in the first place—Shiite identity, sectarian grievance, transnational religious networks, and the concentration of Shiite populations in strategically important territories—appear to persist substantially unchanged.

This suggests that while the specific organizational form of the axis may not be reconstituted, new Shiite-centered political movements and military organizations may emerge in its place.

These new organizations might differ from the axis in important respects: they might be more locally rooted and less directly Iranian-controlled, more focused on sectarian community defense than on regional power projection, more responsive to local populations’ immediate needs than to Tehran’s strategic ambitions.

Yet they would likely still mobilize sectarian identity, maintain transnational connections to broader Shiite communities, and position themselves as defenders of Shiite interests against Sunni dominance or Israeli military power.

Futures of Reconstruction: Could the Axis Reconstitute Itself?

The End of the Axis of Resistance—or Just Its Evolution?

The question of whether the Axis of Resistance could be reconstituted in some form hinges on several critical variables, most fundamentally on the capacity and willingness of Iran to rebuild military capabilities and organize new networks, and on the willingness of regional and international actors to permit such reconstitution.

From a military standpoint, Iran’s trajectory suggests significant constraints on near-term reconstitution. The degradation of Iran’s air defense capabilities and ballistic missile production capacity means that for at least 12-24 months, Iran will operate with severely constrained capacity to project military power against Israel or the United States.

The loss of the Syrian land corridor means that even if Iran wished to rearm Hezbollah, the logistics of doing so have become substantially more difficult and time-consuming.

The degradation of Hezbollah’s military capacity suggests that even substantial Iranian rearmament would require years to return the organization to its pre-2024 military capabilities.

Yet from an organizational and political standpoint, reconstitution appears more feasible than strict military analysis might suggest. Iran could potentially rebuild relationships with an Iraqi government that remains substantially Shiite-dominated and maintains ideological affinity with Iranian interests.

The Trump administration’s announced withdrawal of American forces from Iraq could create opportunities for Iran to reconstitute military supply lines and coordinate with Iraqi militias outside American constraint. New leadership could eventually emerge in Hezbollah capable of mobilizing Lebanese Shiite populations around security and political agendas.

Palestinian organizations could potentially reorganize and resume military resistance, though the devastation of 2024 makes this scenario less probable in the near term.

More fundamentally, Iran could adopt different strategies for mobilizing Shiite sectarian identity that place less emphasis on centralized military coordination and more emphasis on local community organization and social services.

Rather than attempting to rebuild a unified command structure comparable to the pre-2024 axis, Iran might support the emergence of more decentralized, locally autonomous Shiite movements that maintain transnational ideological connections while remaining organizationally independent.

This approach might ultimately prove more resilient to military attack, as it would lack the centralized targets that Israeli military operations can readily destroy.

Future Steps: Trajectories for Regional landscapes

Shattered Alliances, Unbroken Communities

The destruction of the axis has created a complex set of challenges and opportunities for regional actors that will shape Middle Eastern geopolitics over the coming years.

US Exit from Middle East: Iran’s Comeback or Strategic Retreat?

For the United States, the primary challenge involves managing the transition from a regional order in which American military dominance and alliance relationships could constrain Iranian influence toward a more uncertain environment in which Shiite populations and Shiite-aligned organizations will retain significant political weight despite the axis’s collapse.

The American withdrawal from Syria and the diminished scale of American military presence in Iraq reflect recognition of these constraints. Yet American policymakers debate whether complete withdrawal serves American interests or instead creates space for Iranian reconstitution.

Saudi’s Iran Thaw: Diplomacy or Shiite Time Bomb?

For Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Arab states, the challenge involves simultaneously maintaining the rapprochement with Iran achieved through the 2023 normalization while addressing the persistent reality of Shiite identity and Shiite-majority or Shiite-minority populations within their borders and across the broader region.

Saudi Arabia views transnational Shiite networks and Iranian influence as fundamentally threatening to Saudi security and sectarian hegemony. Yet the costs of aggressive confrontation with Iran and Iranian-aligned Shiite movements proved prohibitively expensive, particularly as demonstrated by the Yemen conflict’s devastating impact on Saudi Arabia and the regional humanitarian catastrophe it generated.

The emerging Saudi strategy appears to emphasize containment and management of Iranian influence through diplomacy while avoiding the large-scale military commitments that characterized the pre-normalization period.

Israel’s Axis Victory: Triumph or Shiite Phoenix Rising?

For Israel, the axis’s collapse represents a dramatic strategic triumph that has fundamentally altered the military balance in the Middle East. Israeli military capabilities have proven capable of degrading even sophisticated networks arrayed against it.

The removal of the Assad regime eliminates a critical Iranian ally and disrupts Iran’s capacity to coordinate with allies across the region. Yet Israeli strategists recognize that the underlying conditions generating Shiite militancy and sectarian tension persist and that new organizational forms could eventually emerge to challenge Israeli interests.

Israel’s continued military operations against Iranian targets appear designed to maintain maximum pressure on Iranian capabilities and prevent reconstitution of the axis in any form.

Iran’s Axis Implodes: Gulf Pivot or Desperate Rearmament?

For Iran itself, the challenge involves reconceiving its regional strategy in light of the demonstrated limitations of the proxy network approach. Iranian leaders debate whether to attempt to rebuild the axis through massive rearmament and reorganization, or instead to focus on shoring up Iran’s immediate regional position and reducing vulnerability to external military attack.

The degradation of Iran’s air defenses, the vulnerability of Iranian territory to sustained Israeli military operations, and the economic costs of supporting a devastated network of allies all suggest that Iran’s capacity to pursue an aggressive regional strategy has been substantially constrained.

Some Iranian analysts argue for a strategic reorientation emphasizing Iran’s role as a Persian Gulf regional power focused on Iraq and potentially on moderate engagement with Saudi Arabia and Gulf Arab states, rather than attempting to maintain influence across the broader Arab world.

Shiite World After the Axis: Fragmented Communities, Unbroken Networks

For the Shiite communities themselves, the challenge involves navigating a post-axis environment in which they no longer have a unified transnational organizational structure through which to assert their interests. Iraqi Shiites will likely focus on consolidating their position within Iraq’s political and security structures, rather than participating in regional networks.

Lebanese Shiites face the prospect of rebuilding their war-devastated communities and renegotiating their political role within Lebanon’s confessional system in light of Hezbollah’s degradation. Palestinian Shiites and Houthis will need to develop new strategies for asserting their political positions given the loss of the organizational frameworks that previously supported their activities.

Yet these scattered Shiite populations retain transnational connections through religious networks, media channels, and ideological affinity that could potentially generate new forms of organization even absent the formal structures of the pre-2024 axis.

The Question of Sectarian Reconciliation and Regional Order

The End of War, Not of Division

The destruction of the Axis of Resistance has generated optimistic commentary suggesting that the era of sectarian conflict in the Middle East might be concluding.

Proponents of this view point to the Iran-Saudi normalization agreement, the absence of large-scale sectarian militia violence in Iraq since 2017, and the general exhaustion that the region appears to experience following decades of intense conflict.

Yet the more cautious analysts observe that the conditions giving rise to sectarian identity and sectarian grievance remain fundamentally unaddressed.

Sunni-majority states continue to view the rise of Shiite political power and transnational Shiite organization with alarm and concern.

The possibility that Shiite-majority or Shiite-plurality populations in Iraq, Lebanon, Bahrain, and elsewhere might assert greater control over their own political destinies remains fundamentally threatening to Sunni-led regional powers invested in sectarian hierarchy.

The narrative of Shiite victimization and persecution, which animates Shiite sectarian identity, reflects real historical experiences of Shiite minorities oppressed by Sunni majorities and Sunni-led states.

These underlying asymmetries and grievances are unlikely to be resolved through the destruction of any particular military alliance or organizational network.

The realistic challenge for regional peace appears to involve developing mechanisms through which Shiite communities can assert their interests and identities within inclusive political frameworks, rather than expecting sectarian identity itself to fade from regional politics.

This might involve constitutional arrangements protecting minority rights in Sunni-majority states, power-sharing arrangements that ensure Shiite representation proportional to populations, and international frameworks that protect sectarian communities from majoritarian persecution.

Such arrangements would require sustained diplomatic effort, commitment from regional and international actors to supporting inclusive governance, and mechanisms for addressing historical sectarian grievances rather than simply moving past them.

Conclusion

Living with Sectarianism Rather Than Overcoming It

The Axis of Resistance has been militarily decimated, organizationally disrupted, and strategically disoriented by the cascade of Israeli military operations, the collapse of the Assad regime, and the degradation of Iran’s capacity to project power across the region.

Conventional analysis of these developments frequently concludes that sectarian politics in the Middle East are entering a period of decline or terminal resolution. Yet this analysis fundamentally misunderstands the distinction between specific organizational forms in which sectarian identity is mobilized and the deeper structures of sectarian identity itself.

The Shiite identity that animated the axis rests on theological belief, historical narrative, family and kinship connection, and community institution. These foundations, while damaged by military operations and organizational destruction, have not been eliminated.

From Victory to Inclusion: The Real Test of Middle Eastern Peace

The hawzas of Najaf and Karbala continue to educate young Shiites in religious law and sectarian identity. Shiite families continue to commemorate Ashura and transmit narratives of sectarian victimization and resistance to new generations.

Shiite-affiliated social service organizations continue to provide education, healthcare, and welfare to Shiite populations. Transnational media networks continue to disseminate narratives connecting Shiites across borders and affirming their participation in a broader sectarian community.

The critical implication of this analysis is that while the Axis of Resistance as a specific organizational and strategic construct appears unlikely to be fully reconstituted in its pre-2024 form, the underlying conditions that generated the axis will persist and potentially generate new organizational expressions of Shiite political identity.

Future Shiite-centered political movements might differ in important respects from the pre-2024 axis—they might be more locally rooted, less directly Iranian-controlled, and more focused on sectarian community interests than on regional power projection.

Yet they would likely still mobilize sectarian identity, maintain transnational connections, and assert Shiite interests against what they perceive as Sunni dominance or external military threat.

For regional peace and stability, the implications of this analysis are sobering. Rather than expecting sectarianism to fade with the destruction of the axis, regional and international actors should instead focus on developing political, constitutional, and security arrangements that accommodate sectarian identity and allow sectarian communities to assert their interests within inclusive frameworks.

The alternative—attempting to eliminate sectarian organization through military means while ignoring the underlying sectarian identities and grievances—has repeatedly failed and appears unlikely to succeed in the future.

The region’s future stability may depend less on definitively defeating sectarian movements than on creating political conditions in which sectarian communities need not resort to militancy to assert their interests and preserve their identity.