Zimbabwe’s Socio-Economic and Political Environment: Historical Context and Current Challenges

Introduction

Zimbabwe’s contemporary challenges are deeply rooted in its complex colonial history and the political decisions made since independence in 1980.

FAF, Africa.Media analysis of the trajectory requires examining the pre-colonial foundations, colonial disruption, liberation struggle, and post-independence era that have shaped today’s crisis.

Historical Foundation

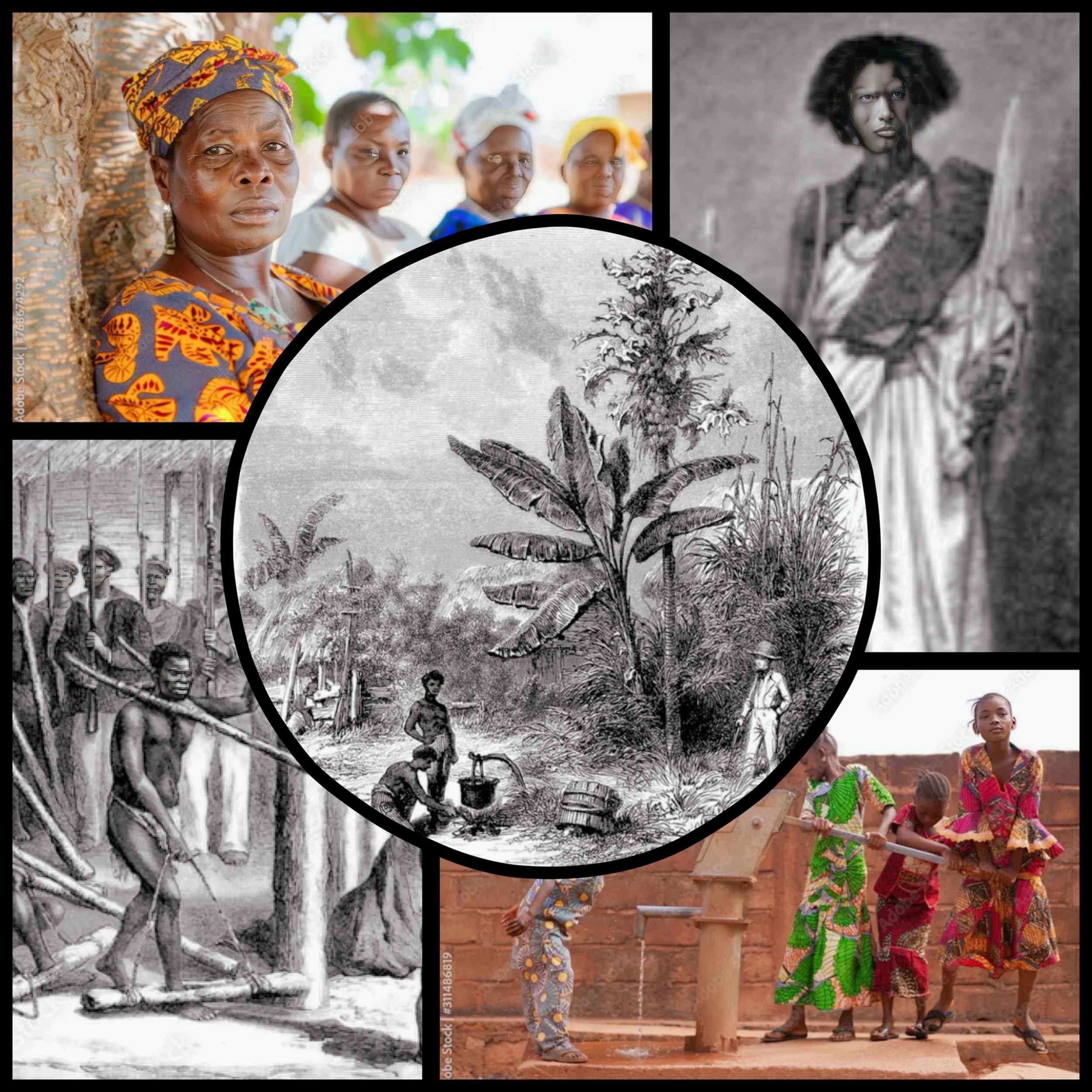

Pre-Colonial Zimbabwe

Before European colonization, the region now known as Zimbabwe was home to sophisticated African kingdoms and trading empires that flourished for centuries.

The San people initially inhabited the area, dating back over 100,000 years. They were followed by Bantu-speaking peoples from around 150 BC, who established agricultural chiefdoms starting in the 4th century.

The most significant was the Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe, which flourished from approximately 1220 to 1450 and gave the modern country its name.

At its peak, Great Zimbabwe covered 7.22 square kilometers and became a major center for industry and political power, with a population of around 10,000 to 20,000 people.

The kingdom developed an economy based on cattle husbandry, crop cultivation, and extensive trade networks that reached as far as China. It primarily traded in gold and ivory.

Other important pre-colonial states included the Mapungubwe Kingdom, the Mutapa Kingdom, the Rozvi Empire, and various smaller chiefdoms.

These societies demonstrated sophisticated political organization, advanced metallurgy, and extensive trade networks that connected the interior with the Indian Ocean coast.

Colonial Era (1890-1980)

The colonial period began in 1890 when Cecil Rhodes’s British South Africa Company (BSAC) invaded Mashonaland through the Pioneer Column.

Rhodes obtained mining concessions from local rulers through treaties like the Rudd Concession in 1888.

However, these agreements were often misunderstood by African leaders who believed they were signing friendship treaties rather than ceding sovereignty.

The colonial system was established through military conquest, including the First Matabele War (1893-1894) and the Second Matabele War (1896-1897), subjugating the Ndebele and Shona peoples.

The territory was named Rhodesia in 1895, and by 1923, it became the self-governing Colony of Southern Rhodesia under British oversight.

Colonial rule fundamentally restructured Zimbabwean society through land seizure forced labor systems, and racial segregation.

By independence, 4,400 white Rhodesians owned 51% of the country’s land, while 4.3 million black Rhodesians owned only 42%. This land distribution became one of the most contentious issues in Zimbabwe’s post-independence politics.

The colonial period culminated in the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965, when Prime Minister Ian Smith’s white minority government declared independence from Britain to avoid implementing majority rule.

This led to international sanctions and the Rhodesian Bush War (1964-1979), a liberation struggle fought by African nationalist movements ZANU and ZAPU against the white minority government.

Liberation War and Independence (1964-1980)

The liberation war was primarily fought between two leading African nationalist organizations: the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), led by Robert Mugabe, and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), led by Joshua Nkomo.

ZANU drew most of its support from the Shona-speaking majority, while ZAPU had strong support among the Ndebele-speaking minority.

The war intensified throughout the 1970s, with both movements conducting guerrilla operations from bases in neighboring Mozambique and Zambia.

The conflict caused significant casualties and economic disruption, ultimately forcing the white minority government to negotiate.

The Lancaster House Agreement, signed in December 1979, ended the war and established the framework for majority rule.

The agreement included provisions protecting white property rights and maintaining the existing land ownership structure for ten years.

In the February 1980 elections, Robert Mugabe’s ZANU party won a landslide victory with 57 out of 80 seats, and Zimbabwe gained internationally recognized independence on April 18, 1980.

Post-Independence Political Development

Early Years and Consolidation (1980-1990)

Robert Mugabe became Zimbabwe’s first black Prime Minister in 1980 and later became President in 1987, a position he held until 2017.

Initially, Mugabe’s government focused on racial reconciliation, expanding healthcare and education, and maintaining economic stability.

However, tensions quickly emerged between ZANU and ZAPU, leading to the brutal Gukurahundi campaign (1982-1987).

During this period, the North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade of the Zimbabwean army killed an estimated 20,000 people, mostly Ndebele civilians, in what many consider genocide.

Emmerson Mnangagwa, then Minister of State Security and current President, oversaw this operation.

The Gukurahundi effectively eliminated ZAPU as a political force, with Joshua Nkomo eventually agreeing to merge his party with ZANU in 1987 to form ZANU-PF.

This established ZANU-PF’s political dominance, which continues today.

Economic Decline and Land Reform (1990s-2000s)

Zimbabwe’s economy began showing serious problems in the 1990s due to various factors, including government mismanagement, corruption, and involvement in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s civil war.

The situation deteriorated dramatically in 2000 when the Fast Track Land Reform Program was implemented.

The land reform program seized approximately 20% of the country’s land from white-owned commercial farms and redistributed it to smallholder and medium-scale farmers.

While intended to address historical land inequities, the program was implemented chaotically and often violently, with farm seizures frequently accompanied by intimidation and violence.

The economic consequences were severe. Agricultural production collapsed as many new farmers lacked the experience, resources, and support systems for commercial farming.

This contributed to food shortages, unemployment, and a broader economic crisis that significantly saw Zimbabwe’s GDP contract.

The land reform crisis accompanied the worst hyperinflation in modern history. Inflation peaked at an estimated 79.6 billion percent month-on-month in November 2008.

The Zimbabwean dollar became worthless, forcing the country to abandon its currency in 2009 and adopt foreign currencies, primarily the US dollar.

The Mugabe Era’s End (2017)

Robert Mugabe’s 37-year rule ended abruptly in November 2017 through a military coup.

The crisis was triggered by Mugabe’s dismissal of Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa and apparent plans to have his wife, Grace Mugabe, succeed him.

On November 15, 2017, the Zimbabwe Defence Forces took control of key areas in Harare and placed Mugabe under house arrest.

After widespread demonstrations and pressure from his party, Mugabe resigned on November 21, 2017. Emmerson Mnangagwa was sworn in as President on November 24, 2017.

Current Political Environment

Mnangagwa’s Presidency and Ongoing Challenges

Emmerson Mnangagwa came to power promising economic reforms and political openness, but his administration has faced significant challenges.

He won disputed elections in 2018 and 2023, with both polls criticized for irregularities and restrictions on the opposition.

Mnangagwa faces the most serious challenge to his rule since taking power. Internal divisions within ZANU-PF have emerged over his apparent desire to extend his presidency beyond the constitutional two-term limit.

The ruling party has initiated steps to amend the constitution so that Mnangagwa can run for a third term in 2028.

This has created unprecedented internal opposition within ZANU-PF, with war veterans and senior party members publicly calling for Mnangagwa to step down.

The crisis has led to concerns about potential coup attempts, prompting Mnangagwa to replace key security officials in what appears to be a coup-proofing exercise.

Political Repression and Human Rights

The political environment remains characterized by repression of opposition voices, restrictions on freedom of assembly and expression, and human rights violations.

Journalists and activists continue to face arrest and intimidation, while elections are consistently criticized for lacking fairness.

Public discontent with economic hardship and corruption is widespread, but fear of repression and the lack of organized opposition limit protest activities.

The exodus of skilled professionals and young people has further weakened prospects for political change.

Current Economic Environment

Macroeconomic Instability

Zimbabwe’s economy continues to face severe challenges in 2024-2025. Inflation has surged dramatically, with the Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) currency experiencing annual inflation of 92.1% in May 2025, up from 85.7% in April.

This represents a continuation of Zimbabwe’s chronic inflation problems that have persisted since the hyperinflation crisis of the 2000s.

The country remains highly dollarized, with foreign currency accounts making up 83% of the broad money supply as of December 2024.

While USD-denominated inflation is lower at 14.4% annually, the dual currency system creates significant economic distortions.

Economic Structure and Performance

Despite these challenges, Zimbabwe’s economy is expected to recover in 2025. GDP growth is forecast to rebound to 6% in 2025, driven by agriculture, recovery from mining (especially lithium and gold), and improved electricity supply.

The economy is led by retail, mining, manufacturing, agriculture, finance, and ICT sectors. Zimbabwe is particularly competitive in agriculture, agribusiness, tourism, and mining energy transition minerals like lithium.

However, the business environment remains challenging due to power shortages, high taxes, complex regulations, and policy uncertainty.

Over 80% of national income is concentrated in the informal sector, reflecting limited opportunities in the formal economy and the resilience of ordinary Zimbabweans in adapting to economic adversity.

Current Social Environment

Humanitarian Crisis

Zimbabwe faces a severe humanitarian crisis in 2025, primarily driven by climate change impacts. An El Niño-induced drought in 2024 left 7.6 million people urgently needing humanitarian assistance, including 3.5 million children.

The drought caused widespread crop failure and water shortages, severely impacting food security. In April 2024, the government identified 7.1 million people at risk of food insecurity.

Child malnutrition rates have risen significantly, particularly in both urban and rural areas.

Social Challenges and Migration

The ongoing economic crisis has led to significant emigration, especially among educated professionals in the health and education sectors.

This brain drain undermines essential services and deepens the country’s social challenges.

The combination of economic hardship, political repression, and limited opportunities has created a cycle where those with the means to leave often do so, further weakening the country’s human capital base.

Public health emergencies, including cholera and polio outbreaks, have added to the social strain.

The healthcare system struggles with limited resources and the departure of qualified professionals.

Conclusion

Current Challenges and Future Outlook

Climate Resilience

Climate change poses one of the most significant long-term challenges for Zimbabwe.

The country’s agriculture-dependent economy is highly vulnerable to droughts and other climate shocks.

Urgent investment in climate resilience and adaptation is needed to protect livelihoods and food security.

Political Transition

The current succession crisis within ZANU-PF represents both a challenge and a potential opportunity for political change.

However, given the party’s history of resolving internal disputes through force or manipulation, genuine democratic progress remains uncertain.

Economic Recovery

While economic growth is forecast to improve, Zimbabwe’s recovery depends on addressing fundamental issues, including currency stability, policy consistency, and governance reforms.

The country’s high debt levels and limited access to international finance further constrain recovery prospects.

Zimbabwe’s path forward requires addressing climate resilience, achieving macroeconomic stability, and implementing genuine political reforms.

However, entrenched interests and persistent governance challenges make meaningful progress difficult.

The country’s rich history and resilient population provide a foundation for recovery, but overcoming decades of mismanagement and building sustainable institutions remains a formidable challenge.